Tinubunomics: Is the tail wagging the dog?

Feature Highlight

Why long-term vision should drive policy actions in the short term to achieve a sustainable Nigerian economic recovery.

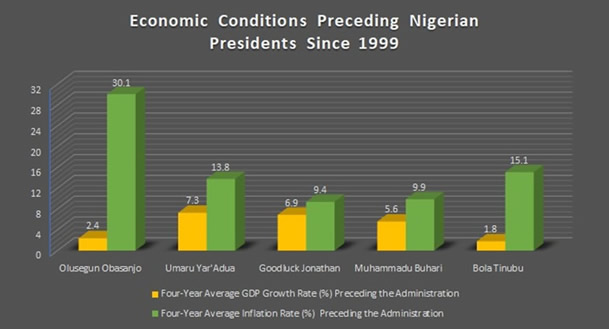

Presidents Olusegun Obasanjo and Bola Tinubu inherited the worst economic challenges so far in the Fourth Republic. According to World Bank data, in the four years preceding each of the five presidencies since 1999, Obasanjo and Tinubu met the slowest average gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates of 2.4 percent and 1.8 percent, respectively. In terms of inflation rate, the four-year average preceding the administration of President Obasanjo was a sky-high 30.1 percent, while that of President Tinubu was 15.1 percent.

The average GDP growth rates and inflation rates, in the four years preceding the other three administrations, were respectively 7.3 percent and 13.8 percent for President Umaru Yar’Adua, 6.9 percent and 9.4 percent for President Goodluck Jonathan, and 5.6 percent and 9.9 percent for President Muhammadu Buhari. President Jonathan arguably inherited the best combination of economic growth and price stability.

It is, therefore, valid the complaint by the Tinubu administration that it inherited challenging economic conditions. He should have known this would be the case while seeking to become President in 2023. What is important now is whether he can fix the economy or not. Compared to Tinubu, President Obasanjo met the worst economic conditions, especially if in addition to the aforementioned data we factor the fact that the Brent Crude oil price averaged $19.4 per barrel in 1999, while it averaged $83.0 per barrel in 2023. Yet, Obasanjo initiated an economic turnaround that extended to the Yar’Adua/Jonathan presidency. For instance, the Excess Crude Account, a fiscal savings account established by Obasanjo, had $20 billion balance in 2009, before it fell sharply under Jonathan to $2.5 billion in December 2014.

World Bank data composed by Financial Nigeria

Initiating long-term economic recovery

President Obasanjo provided apposite empirical frameworks for fostering long-term economic recovery in Nigeria. Many of his policies are instructive for the current administration. This is in the important sense that similar economic challenges being faced by the current administration have been reasonably addressed in the past with major successes.

First, it is important to prioritise reforms that will stabilise the economy over the medium- to long-term. It took Obasanjo some time to enact such a holistic reform agenda, through the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) in 2004. NEEDS was anchored on the private sector as the engine of growth for wealth creation, employment generation, and poverty reduction. This became an enduring economic thinking for the next 11 years until President Buhari started to exercise statist control over the economy when he came into office in 2015, while also anchoring the welfare of the citizens on so-called social investment programmes. Both strategies failed woefully.

Second, expertise matters. President Obasanjo struggled to constitute an appreciably technocratic cabinet during his first term. But during his second presidential term beginning in May 2003, many experts – of world-class intellectual and professional pedigrees – were appointed into his cabinet and important extra-ministerial positions. They focused on long-term solutions to the immediate challenges the country was facing. For instance, the poorly funded public pension system was reformed into a contributory pension system, which mandates coverage for private sector workers, and provides a framework for pooling a large savings fund for long-term investment. From a position of liability, the total pension assets had grown to N18.4 trillion as of December 2023. Also, the decision to bolster bank capital to support the growing private sector has demonstrated long-term impact, providing the pillar for financial stability and the resilience of the banking sector.

Third, Obasanjo cemented his national outlook by embracing ethnic diversity in his appointments. This is always important for an ethnically diverse country like Nigeria, where apart from the existence of hundreds of ethnic nationalities, three of them are dominant and none is domitable by any of the other two. Embracing the country’s diversity helps in fostering political stability, which is a requirement for implementing difficult but beneficial economic reform – at least in a frontier emerging market like Nigeria – where political and market institutions are still weak.

The fourth lesson is the need to balance external reform advice with local reality. It is definitely important, again for a frontier market like Nigeria, to enjoy the support of international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). However, the difficult reform agenda of these institutions need not be front-loaded by a new administration, given the all-too-common social backlashes such reforms generate. In this regard, the government would have to pick and choose the reforms that support market stability and growth, while keeping discussions on the more difficult reforms going forever.

Tinubunomics

Quite clearly, President Tinubu has been zealous in reforming Nigeria’s governance and market frameworks. Before he became President, he often expressed grand ideas in pithy tones. This could have served a strategic value in attracting public attention to himself in the crowded Nigerian political field. Nonetheless, it was surprising that he would launch policymaking in his administration in the bombastic fashion of his political rhetoric. In his inaugural, he grandiloquently declared: “subsidy is gone.” And he followed this policy that has spelt difficulty for the majority of the people with an equally inflationary market exchange rate policy. The combined effects of the two policies are now causing the President and almost all Nigerians sleepless nights.

But Tinubu is no market ideologue. On the very vexed policy of petrol subsidy, he mobilised public opposition to its removal in 2012. But in 2023, as President, he wasted no time in removing the subsidy. While he may have been briefed as incoming-President on how the subsidy had become unsustainable, he probably wanted to make a statement about his political will to take difficult economic decisions. The latest validation of this view is the move by the President to implement the Oronsaye Report that recommends the consolidation of ministries, agencies, and departments (MDAs) of the government. After appointing a large cabinet, President Tinubu has now moved to shrink the bureaucracy, mindful of the high cost of governance.

Thus, Tinubunomics, i.e., President Tinubu’s economic philosophy and key policy actions, has so far been based on exigencies. Politically, he is a survivor – the leading light among the governors that came into office in 1999. He appears to know instinctively and strategically what to do to get a respite from a difficult situation. Translated into economic policymaking, he can – as he has done – start out on market principles and continue on large social spending, thereby standing for and against the market ideology. Therefore, the preponderance of short-term measures he has taken in addressing the economic challenges he met in office and the ones caused by his earlier policy stances are philosophically contradictory.

Need for economic vision

There is the temptation to depend on short-term measures under the current economic trifecta of high inflation, rising unemployment, and weak economic growth – which combined pose a threat of unleashing social discontent. But this will be a mistake. While short-term economic policy measures – and goals – are always useful, they cannot optimise long-term economic stability and growth. Short-term policies are relevant in pursuing long-term economic vision and goal. A long-term goal is the dog that should wag its tail, not the tail wagging the dog.

To frame it in a politically congenial fashion, a long-term vision to transform Nigeria into a leading global market over the next few decades is appropriate today. The first requirement of this is to roll back the Buhari-era statist economic control, not unbridled introduction of inflationary market policies. However, looking closely at Tinubu’s cabinet, he gives a pointer to a likely economic vision by consolidating health and social welfare and then appointing a leading expert to head the so-named ministry. But we have subsequently seen very little to suggest a strong integration of this putative vision into the core agenda that the government seems to be pursuing. A long-term vision of strong social welfare for Nigerians would require enormous wealth creation over the next decades. Such an outcome would equally require enormous investments that can create lasting and transformational impacts.

Pursuing long-term goals

In the first few weeks of this administration, there were glib talks about what it will achieve over the next eight years. That was politics, and it was bound to generate counter politicking – and have politicians eyeing the 2027 presidential race, therefore, beating the gun. But regardless of the framing of the administration’s long-term vision, if it is well advised, the following goals must be pursued to achieve it.

First is a national reorientation towards a great Nigerian future. This is not a novel solution, but the requirement is more fundamental than producing and airing radio and television jingles as previous efforts only did. It entails inculcating what would be Nigerian ideals, shared values, and professional ethics in Nigerians beginning with the government. It would go beyond implementing Oronsaye Report, to instilling the psychology of service in public officials and the bureaucracy, bringing total emoluments of public officeholders – especially members of the National Assembly – into alignment with our national realities and their status, and fostering excellence in service quality.

Second is investment in public health and healthcare delivery. A healthy nation, it is said, is a wealthy nation. The nation needs to address the trauma of the massive deprivation and social retrogression of the citizens in the past few years. The ‘japa’ syndrome has been an alternative therapy for Nigerians who can afford it. But most Nigerians should feel that they can live their best lives in the country – not abroad. Beyond this, the healthcare sector holds immense opportunities for investment across its value-chain, which will generate decent, middle-class jobs and serve a large domestic market and other Ecowas countries that have traditionally relied on Nigeria for pharmaceutical products.

Third, the country must invest in education. International policyspeak has concentrated concerns about lack of education in Nigeria on out-of-school children. Those children, now estimated at over 20 million, need to be enrolled in schools. Also, the concerns have overwhelmingly been that the children who lack the basic-level education are “ticking time bombs.” Very little policy-thoughts have been given to the kind of parents that won’t climb mountains and cross oceans to have their children educated and what to do about the situation. Many of such parents surely place little value on education, either being uneducated themselves or they think there are other routes to socially-acceptable adult life – like marrying off their adolescent girl children. But violence and conflict have definitely contributed to high number of children who are not attending school.

Generally, the country needs a programme of adult education. This could be delivered using a combination of physical and virtual classrooms, which suggests that such a programme should not be designed only for illiterate populations but also for educated people – for instance, in using public infrastructure like bus stops, zebra crossings, etc.

Fourth, we must invest in technology. The discussion about “tech” and “innovation” needs to broaden in Nigeria – from development of apps and using drones to engineering technologies. National knowhow in these fields is important for lowering the cost of public infrastructure as well as launching the country into the manufacturing of products of innovation for exports.

The fifth requirement in pursuing a long-term economic vision of progress in Nigeria is to foster macroeconomic stability. This requires setting long-term targets – for instance, for inflation. The advanced economies and the emerging markets that anchor long-term inflation expectations tend to achieve and maintain price stability. More broadly, there should be targets for such indices like unemployment rate and poverty rate. While the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) pursues “full employment” as a mandate and inflation rate of “single-digit,” it is necessary for the reserve bank to become more ambitious by stating the figures in exact numbers.

Finally, Nigeria must win the war against corruption. A lot of emphasis has been put on the loss of public funds to looting by public officials. This is devastating enough. But even more catastrophic is how corruption destroys societal values, undermines economic productivity, and impedes shared progress. Despite the visible negative impacts of corruption in our society, the way forward on anticorruption in Nigeria is unclear after years of misuse of the anticorruption agency Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), disregard of credible elections, and the continuing rape of judicial justice. It is corruption that undermines the rule of law. Thus, to seriously fight corruption is to assert the rule of law.

Righting wrongs

President Tinubu may have the required mental acuity for delivering his responsibilities to the country and its people. But he still needs experts to help finetune his economic vision and policies. However, the view that his cabinet is lacking in the adequate level of technocratic competence, which may be a case of the number of his ministers that, unarguably, are technocrats, is now gaining ground following what is now an economic implosion that policymakers have been unable to stop and reverse.

But, perhaps, there are enough technocrats in the cabinet. However, appointing expert technocrats is not enough. It matters if they have the right portfolios and if they are not wittingly or unwittingly made less relevant compared to the expert partisans.

As the Tinubu administration nears its first anniversary, the President needs to assess the capacity of his cabinet vis-à-vis the need for long-term transformation of the country. The people cannot manage to cope much longer with short-term policy measures that are unable to deliver sustainable economic impacts. The early to mid-2000s have been referred to as the golden era for policymaking in Nigeria, with great results in telecoms, banking, public debt management, and the country’s institutional architecture. This should not be surprising with the presence of such technocrats as Ernest Ndukwe as Executive Vice Chairman and CEO of Nigerian Communications Commission, Fola Adeola as Chairman of National Pension Commission which he helped to establish, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala as Finance Minister, and Chales Soludo as CBN Governor.

Other corrective measures the President needs to take include greater inclusivity of his government in line with the spirit and not merely the letter of the federal character policy. He should mandate the development of a comprehensive economic policy, à la NEEDS, to bring coherence to policy formulation.

The pivot to market policy by President Tinubu is necessary. But a fundamentalist approach to market policy can have grave consequences and should be jettisoned. While ensuring that his short-term measures to address the impact of the policy actions already taken are effective – especially regarding provision of grants and conditional cash transfers to the poor and vulnerable – the President must formulate and pursue a well-informed long-term vision, which are what the country and the economy need. In this regard, Financial Nigeria is organising the Nigeria Development and Finance Forum (NDFF) 2024 Conference to be held on 8 – 9 May, at Transcorp Hilton, Abuja, to provide actionable insights for addressing the need for long-term economic and social welfare transformation in Nigeria. The conference website is www.ndffconference.com.

Jide Akintunde is Managing Editor, Financial Nigeria Publications, and Director, Nigeria Development and Finance Forum.

Other Features

-

Can you earn consistently on Pocket Option? Myths vs. Facts breakdown

We decided to dispel some myths, and look squarely at the facts, based on trading principles and realistic ...

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

-

Trade-barrier analytics and their impact on Nigeria’s supply ...

Nigeria’s consumer economy is structurally exposed to global supply chain shocks due to deep import dependence ...

-

A short note on assessing market-creating opportunities

We have researched and determined a practical set of factors that funders can analyse when assessing market-creating ...

-

Rethinking inequality: What if it’s a feature, not a bug?

When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots ...

-

Are we in a financial bubble?

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets.

-

Powering financial inclusion across Africa with real-time digital ...

Nigeria is a leader in real-time digital payments, not only in Africa but globally also.

-

Analysis of NERC draft Net Billing Regulations 2025

The draft regulation represents a significant step towards integrating renewable energy at the distribution level of ...

-

The need for safeguards in using chatbots in education and healthcare

Without deliberate efforts the generative AI race could destabilise the very sectors it seeks to transform.

Most Popular News

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Africa needs €240 billion in factoring volumes for SME-led transformation

- ChatGPT is now the most-downloaded app – report

- Green economy to surpass $7 trillion in annual value by 2030 – WEF

- CBN licences 82 bureaux de change under revised guidelines