Rethinking inequality: What if it’s a feature, not a bug?

Feature Highlight

When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots upward.

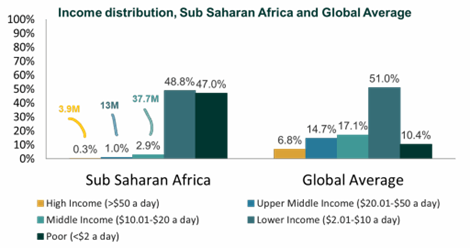

Despite the global economy growing by more than 10x since 1980, from $11 trillion to over $110 trillion, today only 7% of the global population live on more than $50 a day – roughly $18,250 a year. That amount is barely above the poverty guideline for a single person in the United States. Most of the income and wealth created has gone to the top earners.

Source: Pew Research Centre

The richest 10% of the global population take home 52% of the world’s income, while the bottom 50% take home just 8.5%. What’s even worse than income inequality is wealth inequality. The top 10% own 76% of all wealth generated while the bottom 50% own just 2%, according to research from the World Inequality Lab. And as important as income is, wealth is what enables most people to manage shocks and build more resilient lives.

The 2025 Oxfam report on inequality, Takers, Not Makers, describes how wealth for the richest continues to skyrocket, with the expectation of five trillionaires within a decade, while the number of people living in poverty globally hasn’t budged since 1990.

The solution is often to expose and shame the rich, call for increased taxes on them, and then to redistribute income and wealth more equitably. The impulse is understandable and perhaps even noble. The only problem is that it isn’t working. Worse still, it is unlikely to ever work.

Since Oxfam released its first report on inequality, global inequality has increased significantly. Since 2015, the wealth of the top 1% has surged by over $33.9 trillion, according to Oxfam’s findings. “The wealth of just 3,000 billionaires has surged $6.5 trillion in real terms since 2015, and now comprises the equivalent of 14.6 per cent of global GDP,” one of their reports notes. It also notes that billionaire wealth is growing at a faster rate than in previous years.

With the advent of artificial intelligence, mounting fiscal pressures, and rising nationalism, this trend is likely to intensify rather than reverse.

The mechanism we rely on to fix inequality, the government, is itself deeply entangled in it. Those with the greatest influence over taxation and redistribution are often the very people who benefit most from the current system. Expecting such a structure to take from itself and give to others is unlikely to lead to major reform.

If redistribution cannot deliver, then perhaps the solution lies elsewhere, not in taking from the top, but in redesigning how the entire system functions.

A different way to think about inequality

What if we are thinking about inequality all wrong? What if we thought about inequality as a feature and not a bug?

In her book, Thinking in Systems, the late Donella Meadows reminds us that highly functioning systems have three characteristics: resilience, self-organisation, and hierarchy. It’s the characteristic of hierarchy that’s important here.

Meadows reminds us that “the original purpose of a hierarchy is always to help its originating subsystems do their jobs better. This is something, unfortunately, that both the higher and lower levels of a greatly articulated hierarchy can easily forget. Therefore, many systems are not meeting our goals because of malfunctioning hierarchies.”

In effect, Meadows is describing how well-functioning systems, from forests and coral reefs to families and schools, exhibit this quality: those with more exist to serve those with less.

In a tree, roots empower the leaves while the leaves sustain the roots. The trunk and branches are intermediaries of exchange and balance. When any layer becomes parasitic, taking more than it gives, the system weakens. Disease spreads, growth halts, or collapse follows.

Consider the following examples.

In well-functioning systems, the healthiest hierarchies exist not to dominate but to serve. For instance, concrete and steel exist to serve glass and wood. The goal then should not be to take from steel or concrete and give to glass and wood.

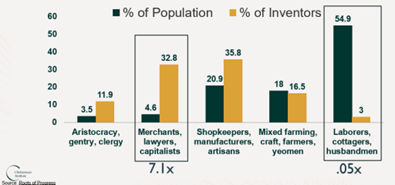

Share of population responsible for inventions during the British Industrial Revolution

The same is true for societies. The goal is not to take from the rich and give to the poor, but to design systems in which those with more – wealth, knowledge, or capacity – exist to serve those with less. That is how the natural world sustains itself and how healthy economies grow. When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots upward. This is the essence of market creation, which I have written plenty about.

Inequality, then, is not our greatest danger; it might just be our greatest opportunity to build systems that serve rather than exploit.

Efosa Ojomo is a senior research fellow at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation, and co-author of The Prosperity Paradox: How Innovation Can Lift Nations Out of Poverty. Efosa researches, writes, and speaks about ways in which innovation can transform organisations and create inclusive prosperity for many in emerging markets.

Other Features

-

Can you earn consistently on Pocket Option? Myths vs. Facts breakdown

We decided to dispel some myths, and look squarely at the facts, based on trading principles and realistic ...

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

-

Trade-barrier analytics and their impact on Nigeria’s supply ...

Nigeria’s consumer economy is structurally exposed to global supply chain shocks due to deep import dependence ...

-

A short note on assessing market-creating opportunities

We have researched and determined a practical set of factors that funders can analyse when assessing market-creating ...

-

Are we in a financial bubble?

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets.

-

Powering financial inclusion across Africa with real-time digital ...

Nigeria is a leader in real-time digital payments, not only in Africa but globally also.

-

Analysis of NERC draft Net Billing Regulations 2025

The draft regulation represents a significant step towards integrating renewable energy at the distribution level of ...

-

The need for safeguards in using chatbots in education and healthcare

Without deliberate efforts the generative AI race could destabilise the very sectors it seeks to transform.

-

Foundation calls for urgent actions to tackle fake drugs and alcohol

Olajide Olutuyi, Executive Director, Samuel Olutuyi Foundation, warns: “If left unchecked, the ‘death ...

Most Popular News

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Afreximbank backs Elumelu’s Heirs Energies with $750-million facility

- AfDB and Nedbank Group sign funding partnership for housing and trade

- GlobalData identifies major market trends for 2026

- Lagride secures $100 million facility from UBA