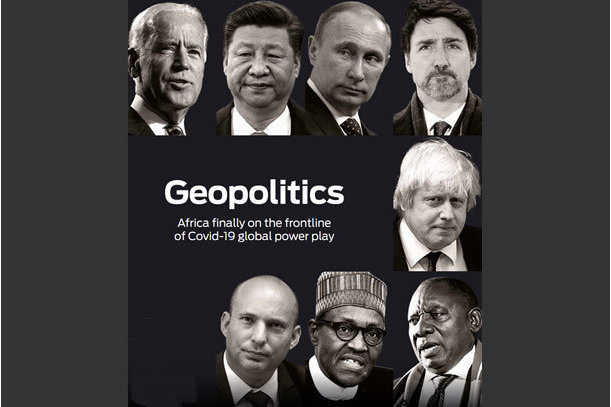

Geopolitics: Africa finally on the frontline of Covid-19 global power play

Feature Highlight

Africa needs to counter its global geopolitical weakness. This has little to do with having prejudicial travel bans against the continent overturned.

With the inauguration of Joe Biden as US President in January last year, following the banning of his predecessor former President Donald Trump from Twitter, geopolitics appeared to simmer during the year. But this was just an appearance, given Biden’s gentlemanly mien. The politics of international relations, as influenced by geographical factors, is not always conducted over megaphones like Trump did while he occupied the White House. 2021 was no less geopolitically significant; indeed, it was one of realignment, given the big effort the US needed to muster in its determination to contain China’s rise on the global stage.

During the year, the Covid-19 pandemic was a major instrument of geopolitics as it had been since the outbreak in 2019. Distribution of vaccines against the virus and travel restrictions featured prominently as tools of geopolitics in 2021. Africa, in particular Sub Saharan African (SSA) countries that had been at the margins of the global power dynamics of the pandemic, happy with the pity party the rest of the world throws for it, suddenly came on the frontline.

Covid-19 is not going anywhere soon. It is, therefore, important to trace the geopolitical trajectory of the pandemic and offer clues on how Africa may be impacted, or better still how the continent can begin to chart a different path away from its current unambitious position that is by no means limited to its poor response to the pandemic. The Omicron variant of the virus has now forced a reset of Covid-19 response.

Before the discovery of the new variant last November, the rich countries had started to develop policy strategies to live with coronavirus. Lockdown and travel restrictions were being replaced by vaccination campaigns, including booster shots for those already fully vaccinated to enhance their immunity. The economies were to remain fully reopened and everyone looked forward to happy reunion with their family and friends for Christmas. But Omicron forcefully reintroduced the old realities of the pandemic, and the crass geopolitics of major viral disease outbreaks.

Historical Contours

There are striking parallels between Covid-19 and 1918 Spanish flu pandemics. For starters, the origins of both are unknown – or, as they remain, disputed. Like Covid-19, the Great Influenza epidemic, as the Spanish flu is also known, required the use of face masks and restriction of movement to slowdown or prevent its community transmission. With the Omicron variant now spreading like wildfire around the world, and perhaps deadlier future variants, Covid-19 – which has recorded over 270 million cases worldwide – may well become as devastating as Spanish flu, which infected over 500 million people, representing a third of the world’s population as of then, and killed up to 50 million people.

Spain was stigmatised for giving the Spanish flu to the world, but scientific consensus later emerged that the disease did not originate from the country. The country that originated the H1N1 virus that caused the deadly influenza disease remains unknown for sure, till today. It has been suggested that the virus originated in France, China, Britain or the United States, where the first known case was reported at a military base in Kansas on 11 March 1918. And, believing that the virus had spread to their country from France, Spain rechristened the virus the “French flu.” The nomenclature, which was irrelevant to containing the outbreak, served only to stigmatise – and it could have led to ‘reprisal’ military attacks.

The prospects of such mistaken attacks loom large today for any country that is vulnerable to it, especially with the various experimentations with biological organisms – including as potential weapons. The spread of Covid-19 has also been countered by “isolation”, either of self when infected, or of countries through travel ban. A more terrifying prospect of isolation of a country that originates a more virulent variant of coronavirus remains.

As great countries do, China must have learnt from the world’s history, of naming a pandemic viral outbreak to shame the country that is believed to originate it. Therefore, although the first cases of SARS-CoV-2, the scientific name for Covid-19, were discovered in Wuhan, Hubei province of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in December 2019, the country has resisted, and rejected out of hand, any indication that the virus originated within its borders.

Nevertheless, President Trump called Covid-19 the “Chinese virus” at a time he was ratcheting up US trade war with China. Trump’s demagoguery – and even racism and xenophobia as his christening of Covid-19 has been interpreted to mean – stretches the imagination on the possible fate of a geopolitically weak country that may originate a pandemic. Not only was his attempt to stigmatise China with the virus a geopolitical game, but it also served as red meat for energising his political base at home, indicating such leader can go to any length just to hold on to power.

Vaccine Diplomacy

The race to develop vaccines for Covid-19 broadened the canvass of the geopolitics of the pandemic. Ultimately, countries were either vaccine producers, buyers or African – relying on the largesse of the rich countries to access meagre numbers of doses. Russia raced ahead of its Western rivals by registering Sputnik V on 11 August 2020 as the world’s first vaccine for Covid-19, developed by one of the country’s research institutes. The feat fitted the narrative of President Vladimir Putin who had been hankering for the return of the “glorious” years of the Soviet Union.

However, the vaccine was subscribed by few countries outside the West, such as Argentina, Belarus, Hungary, Serbia and Pakistan. The Philippines and the United Arab Emirates, keen to maintain broad international relations, also ordered the Russian vaccine. But the first-mover advantage of the vaccine was quelled. Emergency use authorisations were granted a cohort of vaccines developed by the major Western drug makers, including Pfizer, Moderna, AstraZeneca, and Johnson & Johnson two weeks after Sputnik V was approved. Today, the narrative that it took nine months to develop and approve a vaccine against a viral infection fitted more the timeline for the Western vaccines, undercutting the miraculousness of the development of the Covid-19 vaccines generally.

Beggarly Diplomacy

Africa, which accounted for 2% of global GDP in 2020, and had no significant capacity for vaccine production, had been ignored in the power dynamics of developing the Covid-19 vaccine. Perhaps the real miracle till date is that Africa has been somewhat resilient to the pandemic – if not based on low case count presumed to be due to low rate of testing, but certainly because of the relative low number of deaths from the infection. As of last Christmas, Africa had accounted for only 4.2% of the global fatality to Covid-19, compared to 27.9% by Europe, 22.8% by North America, 23% by Asia and 21.9% by South America.

The first brunt of the geopolitics of the pandemic by Africa was borne by the Ethiopian biologist and public health expert, Dr. Tedros Ghebreyesus, the Director General of the World Health Organisation. President Trump accused the WHO of acting too slowly to sound the alarm about the coronavirus outbreak. From there on, the WHO DG virtually lost his voice on the pandemic, and Trump damaged him further by going ahead to carry out his threat of withdrawing US membership and financial contribution to the world’s health body. Both have now been restored by President Biden.

The second indignity Africa suffered was the highlight of the Western media on the beggarly status of the continent that relies on the charity of the rich nations to have meagre numbers of the vaccines after long wait on the queue. As with the traditional aid system that was in fact choking Africa, the COVAX initiative to deliver Covid-19 vaccine to African countries has had underwhelming impact. With scarcity fuelling hesitancy to vaccination, only 6% of Africa’s population had been vaccinated against Covid-19 as of October 2021 ending, compared to over 70% of high-income countries, according to WHO Africa Regional Office.

Prejudicial Travel Ban

The third and the latest geopolitical backlash Africa has suffered from the pandemic is the travel ban slammed on SSA countries, including Nigeria, following the discovery of the Omicron variant in South Africa. In a reaction that was at best panicked, but more likely prejudicial, Western countries decided to ban air travels from South Africa and other southern African nations with the ban extended further because of the Omicron variant. The variant had been reported in other countries outside the continent by the time the travel bans were announced but no similar restrictions were placed on these other countries.

In any case, the discovery of a variant in a country does not automatically mean it originates there. It could mean, as it is probably the case, that South Africa’s surveillance system for Covid-19 had worked well. The country’s scientists were also able to profile Omicron to the world as being more transmissible but causes less severe illness. Both have so far been validated.

Instead of praise for South Africa, there was a dramatic effort to paint Africa as the ‘origin’ of Covid-19 – at least the Omicron variant. A Spanish newspaper trended on social media for a cartoon which designed the coronavirus in black skin on dinghies heading towards Europe. A German newspaper also ran a headline that translates to calling Omicron the ‘African virus.’ Black Africa had become the object of stigmatisation for Covid-19 that the Western world had been looking for, with another little help from Israel. The country of 9.2 million people announced a travel ban against the entire 1.1 billion people of SSA countries, despite the fact that the new variant (as of then) had only been discovered in some southern African countries.

Countering Geopolitical Weakness

Africa needs to counter its geopolitical weakness. This has little to do with having the travel ban overturned. As Nigerian Covid-19 policymakers correctly observed, it makes no sense that one country would ban travels from some countries while its airlines would continue to fly to these destinations. What African countries should do is to finally start to seriously harness their economic potentials. This means African leaders should stop stealing public funds and stashing them in foreign countries. The continent also needs a new crop of competent national leaders that are visionary and can strategically negotiate the place of Africans under the sun. African countries also need to trade with one another more, under the aegis of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA).

A prosperous Africa will earn respect of the rest of the world because of the meaningful contributions it can make to global prosperity. At no time since the outbreak of the pandemic has China, which accounts for circa 18% of global GDP, been placed on prejudicial travel ban. This is also because of the effective control measures against the spread of the virus in China. In this regard, African countries need to start to prioritise public health and develop capacity to adequately respond to pandemics as part of an overall approach to safeguard the well-being of their citizens.

Conclusion

The geopolitics of Covid-19 has helped the virus to spread more than it would have under different circumstances. Trump’s supporters whom he had wilily discouraged from being vaccinated had to boo him when last month he revealed that he had even taken a booster shot. Vaccine nationalism may also provide opportunity for new mutations of the virus in population with low vaccination protection. Moreover, countries that discover new variants in the future may not follow the good example of South Africa by disclosing the information over concern of possible stigmatisation and other backlashes.

The science of Covid-19 suggests that the pandemic will not finally end in any country as along as the virus continue to spread somewhere else. This calls for true global solidarity. This virus has so far respected poor countries than rich and powerful ones. But everyone is at risk.

Cheta Nwanze is Lead Partner at SBM Intelligence. Jide Akintunde is Managing Editor of Financial Nigeria, and Director, Nigeria Development and Finance Forum.

Other Features

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

-

Trade-barrier analytics and their impact on Nigeria’s supply ...

Nigeria’s consumer economy is structurally exposed to global supply chain shocks due to deep import dependence ...

-

A short note on assessing market-creating opportunities

We have researched and determined a practical set of factors that funders can analyse when assessing market-creating ...

-

Rethinking inequality: What if it’s a feature, not a bug?

When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots ...

-

Are we in a financial bubble?

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets.

-

Powering financial inclusion across Africa with real-time digital ...

Nigeria is a leader in real-time digital payments, not only in Africa but globally also.

-

Analysis of NERC draft Net Billing Regulations 2025

The draft regulation represents a significant step towards integrating renewable energy at the distribution level of ...

-

The need for safeguards in using chatbots in education and healthcare

Without deliberate efforts the generative AI race could destabilise the very sectors it seeks to transform.

-

Foundation calls for urgent actions to tackle fake drugs and alcohol

Olajide Olutuyi, Executive Director, Samuel Olutuyi Foundation, warns: “If left unchecked, the ‘death ...

Most Popular News

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Africa needs €240 billion in factoring volumes for SME-led transformation

- ChatGPT is now the most-downloaded app – report

- Green economy to surpass $7 trillion in annual value by 2030 – WEF

- CBN licences 82 bureaux de change under revised guidelines