Remittances out-performing FDI flows to Nigeria

Feature Highlight

Apart from the volatility of FDIs, this source of development finance comes with finance costs (such as interests, dividends, repayments, and timed/untimed capital repatriations) and non-finance costs (these are conditions intended to achieve the objectives of the investors, irrespective of the domestic consequences).

In the last few months, a lot has been written about the amount of capital flows into Nigeria. By comparing receipts from foreign direct investments (FDIs) with migrant remittances (MRs), this article reviews the volume of Nigeria’s capital inflows in recent years and considers the potential impact of MRs as a source of development finance on Nigeria’s economic growth.

Migrant remittances and FDI flows in recent years

The World Bank defines personal remittances as the sum of (i) the income of seasonal, and other short-term workers who are employed in an economy by non-resident entities, and (ii) personal transfers in cash or in kind made or received by residents from or to individuals in other countries. Depending on the information source, estimates of the number of Nigerians in the diaspora vary from 1.24 million (United Nations, 2017) to between 5-15 million (Nigeriandiaspora.com).

The International Monetary Fund’s Balance of Payments Manual (6th Edition, 2009) defines a foreign direct investment as “a category of cross-border investment associated with a resident in one economy having control or a significant degree of influence on the management of an enterprise that is resident in another economy.”

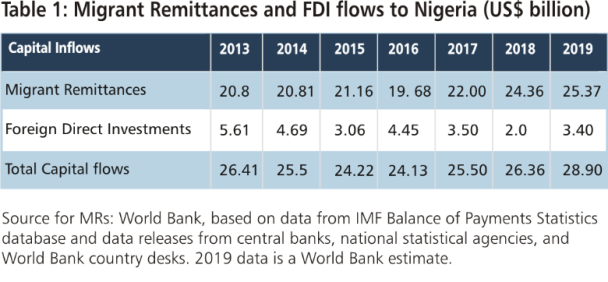

Available data suggests that total capital inflows into Nigeria have been on the rise for a number of years (see Table 1). The World Bank and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) data provide a couple of other insights, viz: (i) year-on-year, migrant remittances are significantly higher than FDIs, accounting for between 78.8 per cent and 92.4 per cent of total capital inflows between 2013 and 2019; and (ii) migrant remittances are at stable-to-rising levels while FDIs are rather more volatile.

Volume of capital inflows as a share of GDP

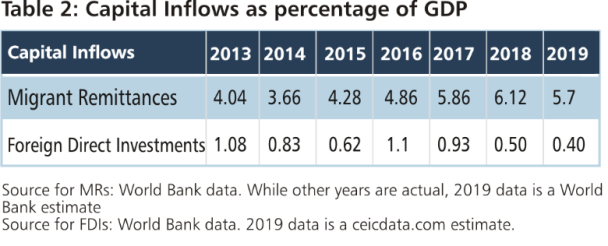

From the foregoing, the value of migrant remittances as a percentage of Nigeria’s GDP is significantly higher than the ratio of FDIs to GDP. In addition, while the percentage of FDIs to GDP has been on the decline since 2017 (see Table 2), the ratio of MRs has been on the rise since 2015. Note that the ratios of migrant remittances and FDIs for 2019 are based on estimates. When finalized, the actual figures and trajectories may differ.

Effect of economic climate on MRs and FDIs

The UNCTAD 2019 World Investment Report shows Nigeria was the third largest host economy for FDI in Africa, coming behind Egypt and Ethiopia. Notwithstanding the 70 per cent growth in Nigeria's FDI inflow last year, evidence shows that migrant remittances over the years have been more significant in volume and more stable.

Irrespective of the prevailing economic situation, the odds are high that migrants would continue to remit funds to family members who depend on such remittances for sustenance. Whereas, private investors avoid making further investments during periods of economic downturns.

Apart from the volatility of FDIs, this source of development finance comes with finance costs (such as interests, dividends, repayments, and timed/untimed capital repatriations) and non-finance costs (these are conditions intended to achieve the objectives of the investors, irrespective of the domestic consequences).

Remittances as a bona fide source of development finance

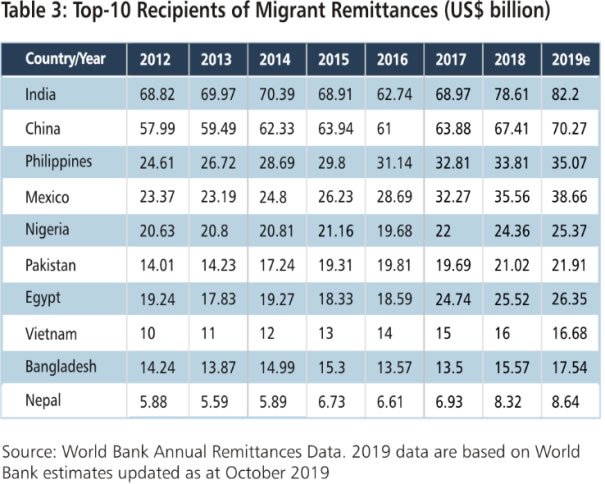

The size of Nigeria's diaspora population – vis-à-vis other sub-Saharan African nations – and the relative stability of migrant remittance inflows provide the country a competitive advantage to attract remittances as a development finance. Available data confirm that Nigeria has remained, for many years, among the top five countries globally for remittance receipts. Indeed, Nigeria alternates in the top position in Africa with Egypt.

See in the below table, the recent trend in migrant remittance inflows for the top 10 remittance receiving countries.

The following are a number of ways Nigeria can position itself properly to maximize the benefits of remittances as a development finance:

i. Securitizing future flow receivables

It is possible for the monetary authorities or national government to issue remittance-backed Eurobonds to raise long-dated external finance, with future migrant remittances as collateral. In a 2001 World Bank research, authors, Suhas Ketkar and Dilip Ratha, found that “developing country issuers could potentially raise about $7 billion a year using future remittance-backed securitization.” To caveat this, it is important to note that a significant amount of remittances is received through unofficial sources and local funds transfer agents. Therefore, the securitization strategy assumes that most of the migrant remittances will be received through the formal financial system such as deposit money banks, bureaux de change, merchant banks, and finance houses.

ii. High margin banking business and additional tax revenue

Financial institutions act as intermediaries in the transfer of funds between the diaspora population and families back home, and charge significant transaction fees for this service. According to the World Bank’s Remittance Prices Worldwide Database, as at 2018, the average cost of sending money to low- and middle-income countries was 7.1 per cent of the amount sent with sub-Saharan Africa having the highest average cost, at 9.4 per cent. According to the bank's Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD, 2018), “remittance costs across many African corridors and small islands in the Pacific remain above 10 per cent, because of the low volumes of formal flows, inadequate penetration of new technologies, and lack of a competitive market environment.”

Over time, banks have also come to realize that while the relationships start as remittance-only, they quickly evolve into providing additional services, such as mortgages, cards services, and referrals. Increase in bank profits as a result of the high margin business also results in more revenue to government in the form of increased tax revenues.

iii. Economic growth

Migrant remittances are critical for economic growth because the inflows spent on consumption create positive multiplier effects as the purchase of locally-produced goods stimulates more local production and employment. Furthermore, remittances that are invested in raw materials, plants and machinery, etc. result in increased employment and output. Hence, government earns income through value added tax (VAT) and other taxes. All things being equal, increased remittances could result in increased household consumption, investments, government revenue and export earnings.

Finally

Without being too theoretical, it suffices to add that a body of research supports the positive effects of remittances on economic growth and its potential to lift people out of poverty. With the Nigerian diaspora population estimated to be at around 15 million, if at least 60 per cent of this number remits an average of $5,000 per annum to Nigeria, that potentially would result in at least $45 billion worth of migrant remittance inflows to Nigeria every year.

The requirements for this to be realizable are a favourable political and business environment, and deliberate policies to encourage diaspora philanthropy, investments, and regular parleys. These will include (but not limited to):

a. Engaging the Nigerian diaspora community and encouraging their involvement in matters of economic growth and development;

b. Mobilizing diaspora remittances and savings for investments to facilitate domestic long-term financing;

c. Removing bottlenecks to migrant remittance inflows such as significant transaction costs, complex/multiple tax regimes, bureaucracies, immigration protocols, customs clearance and challenges to running businesses in Nigeria; and

d. Deliberate inclusion of the Nigerian diaspora in programmes, which encourage return of skilled workers to participate in the programmes.

Tade Oludare PhD, is an economist and a professionally qualified accountant, banker, and stockbroker. He has significant experience working or consulting for financial institutions and the academia in Europe, the United States of America, and Africa.

Other Features

-

Can you earn consistently on Pocket Option? Myths vs. Facts breakdown

We decided to dispel some myths, and look squarely at the facts, based on trading principles and realistic ...

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

-

Trade-barrier analytics and their impact on Nigeria’s supply ...

Nigeria’s consumer economy is structurally exposed to global supply chain shocks due to deep import dependence ...

-

A short note on assessing market-creating opportunities

We have researched and determined a practical set of factors that funders can analyse when assessing market-creating ...

-

Rethinking inequality: What if it’s a feature, not a bug?

When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots ...

-

Are we in a financial bubble?

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets.

-

Powering financial inclusion across Africa with real-time digital ...

Nigeria is a leader in real-time digital payments, not only in Africa but globally also.

-

Analysis of NERC draft Net Billing Regulations 2025

The draft regulation represents a significant step towards integrating renewable energy at the distribution level of ...

-

The need for safeguards in using chatbots in education and healthcare

Without deliberate efforts the generative AI race could destabilise the very sectors it seeks to transform.

Most Popular News

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Afreximbank backs Elumelu’s Heirs Energies with $750-million facility

- AfDB and Nedbank Group sign funding partnership for housing and trade

- GlobalData identifies major market trends for 2026

- Lagride secures $100 million facility from UBA