Improving diaspora remittances into Nigeria

Feature Highlight

Extensive foreign exchange controls restrict access to official exchange markets and lead to expansion of parallel markets.

Introduction

In an earlier article on capital flows to Nigeria published in the April 2020 edition of this magazine, I argued that diaspora remittances are a relatively stable source of foreign exchange as well as one of the least volatile sources of development finance for developing countries. Indeed, available data confirm that migrant remittances to Nigeria have been relatively stable.

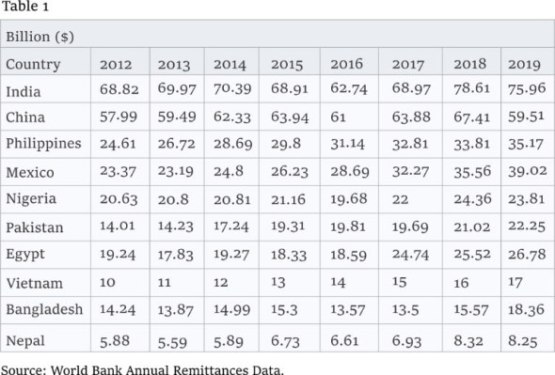

The country has remained for many years a top-six country globally in terms of remittance receipts and alternates the top position in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) with Egypt. (See the following table for the recent trend in migrant remittance inflows for the top 10 remittance receiving countries.)

Foreign Reserves and Exchange Rate Problems

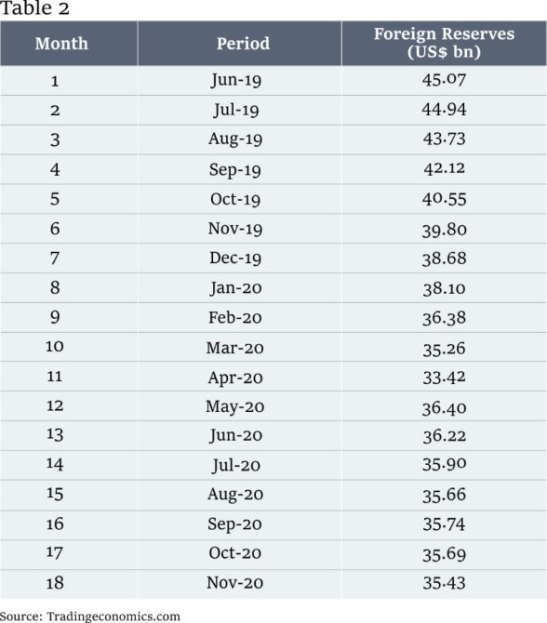

Despite the reported billions of dollars’ worth of diaspora remittances flowing into Nigeria every year, the impact of the capital flows is barely felt. For instance, Nigeria's external reserves continued its decline from the middle of 2019 all the way to the end of November 2020 – based on the latest data available as of the time of writing this article in December. (See Table 2 below).

By May 2020, the month-on-month depletion of the foreign reserves showed signs of respite with an increase from $33.42 billion in April 2020, to $36.40 billion, thanks to the disbursement of the $3.4 billion emergency financial assistance by the IMF to Nigeria to support the country’s efforts in addressing the severe economic impact of the COVID-19 shock amid the sharp fall in oil prices. It can also be observed from Table 2 that in spite of the IMF loan, foreign reserves increased by $2.98 billion. This means that in the absence of the IMF loan, foreign reserves would have declined by a further $420 million.

Amid mounting pressures on the country’s foreign reserves, Table 3 shows consistent annual depreciation of the local currency against the United States dollar. Unfortunately, annual currency depreciations only lead to even more demand for US dollars, leading to the declines in the reserves as can be seen from the data in Table 2.

Ostensibly, tens of billions of dollars are remitted to the country every year coupled with even more billions received from crude oil sales that are usually above the budget benchmark price (except occasionally over the last few years when prices fell below the benchmark). So, how come, then, do the nation’s reserves continue to dwindle and the exchange rate devalued annually?

There are a number of reasons for this. First, experts believe that available data on diaspora remittances to Nigeria are grossly under-reported since much of the funds do not pass through official channels. Hence, the reported data is erroneous as a result of estimation methodology. But there are other reasons beyond inaccurate data – which dovetails into my second point.

International Money Transfer Operators (IMTOs) receive inflows strictly in foreign currencies (mostly US dollars, British pounds, and euros) into offshore bank accounts. However, most of the beneficiaries of these inflows in Nigeria are paid in the local currency (naira) at exchange rates determined by the IMTOs and below parallel market exchange rates.

Therefore, most of the so-called diaspora remittances do not actually get into the country but are rather held in the foreign bank accounts of IMTOs and other transfer agents who take commissions on every money transfer and also make significant foreign exchange gains, while beneficiaries in Nigeria receive their funds in naira.

Thirdly, it is logical to expect that previous monetary policies did not encourage diaspora remittances through official channels. Meanwhile, unofficial channels guaranteed recipients their payments in foreign currencies or at least they could receive the remittances based on market-driven rates rather than bank-determined rates. Consequently, official estimates of diaspora remittances do not cover informal transfers (such as via friends, relatives, unlicensed transfer agents, or transport companies on return trips to the countries of origin). Research has also shown that a significant portion of foreign currency inflows into Nigeria comes in through unlicensed/unregistered money transfer operators who do not have any reporting obligations and willingly offer higher premiums compared to the foreign exchange rates offered by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) or IMTOs.

According to the World Bank Working Paper Number 92 published in 2007, “Nigeria is the largest recipient of remittances in Sub-Saharan Africa [and] receives nearly 65 per cent of officially-recorded remittance flows to the region … [however] … as is the case for other countries in Sub Saharan Africa, underreporting of remittance flows to Nigeria is common because of data collection deficiencies and the prevalence of informal transfer mechanisms. The latter account for 50 percent of total flows to the country.” The World Bank also found that as a result of the largely unknown scope of informal transfers, the official remittance figures are likely to be underreported by as much as 50 per cent.

In a speech by the CBN Governor, Godwin Emefiele, on December 3, 2020, he stated that a CBN investigation into data on IMTO inflows into the country in the previous 12-month period showed sharp practices by some IMTOs. Rather than competing to improve transaction volumes and creating more efficient ways for Nigerians in the diaspora to remit funds, some operators resorted to engaging in arbitrage arrangements on the naira-dollar exchange rate. Such practice, to a large extent, resulted in a significant drop in flows into the country. The CBN investigation also showed the use of unlicensed operators.

Recent Policy Actions

Many research papers have shown that, over time, extensive foreign exchange controls restrict access to the official exchange markets and stimulate the growth and expansion of parallel markets. In responding to the growth of parallel markets, central banks would often further tighten exchange controls, particularly where the official exchange rate continues to deteriorate, thereby perpetuating the vicious cycle. This analysis fits what has been happening in Nigeria over the past five years, as multiple official and parallel exchange rates now exist in the market.

But the CBN has now found scope to bring diaspora remittances into official channels, with potentially positive impact. In the last few weeks, the CBN issued at least four circulars on new procedures for receiving diaspora remittances. The purpose of these circulars, it would appear, is to liberalize, simplify and encourage the receipt and administration of such inflows into the country.

According to the November 30, 2020 circular, CBN directed that beneficiaries of diaspora remittances through IMTOs must receive such inflows in foreign currency through designated banks of their choice. It further stated recipients of remittances may choose to receive these funds in foreign currency cash or into their ordinary domiciliary accounts. A second circular issued on the same day reminded all authorized dealers and the general public that beneficiaries must be given unfettered access and utilization to such foreign currency proceeds, either in foreign currency cash and/or into domiciliary accounts.

A third circular, dated December 2, insisted that IMTOs must deposit all funds in favour of Nigerian beneficiaries into correspondent bank accounts of Nigerian banks. Another circular on December 18 directed that all Nigerian banks close all IMTO naira accounts through which the remittances were, hitherto, being made to beneficiaries in the local currency. This is to ensure all diaspora remittances can only be received by beneficiaries in foreign currency.

Policy Consequences

Several consequences of these new policy are immediately obvious, including: (i) increased diaspora remittance into Nigeria, (ii) increased remittance data accuracy, and (iii) less reliance on official sources of foreign exchange such as revenue from crude oil sales.

But perhaps the most important consequence of the new policy is the likely gradual narrowing of the foreign exchange premium between official exchange rate and parallel market rate as beneficiaries can dispose of their foreign currencies as they please and at rates that are acceptable to them. Beneficiaries are allowed to invest the foreign currencies directly in Nigerian Euro-bonds and foreign currency fixed deposit funds. They can also sell the foreign exchange outright to other third parties, such as importers, bureaux de change, banks and money transfer agents.

While the new policy may not affect foreign reserves directly, increased unofficial supply via diaspora remittances and the increased number of outlets to sell foreign currencies would reduce the pressure of aggregate demand on the foreign reserves. The new policy will also disincentivize round-tripping tendencies and stabilize the exchange rate. Perhaps, this would ultimately lead to unification of the CBN’s multiple exchange rates.

Conclusion

As pointed out in my previous article, one of the benefits of diaspora remittances is that they are critical for economic growth. For example, remittance inflows spent on consumption and investments create positive multiplier effects. When used to purchase locally produced goods, remittances stimulate more local production and employment. Government also earns income from remittances through taxes on consumption, production and profits (where remittances are invested).

Added to these benefits are the positive impact of the new CBN policy, including encouraging the use of official channels for diaspora remittances with the potential effect of more accurate data for development planning.

Notwithstanding how laudable the new policy is, the proof of its effectiveness would be in its implementation. It remains to be seen whether the authorities will monitor the market for full compliance.

Tade Oludare, PhD, is an economist and a professionally qualified accountant, banker, and stockbroker. He has significant experience working and consulting for financial institutions and the academia in Europe, the United States of America, and Africa.

Other Features

-

Can you earn consistently on Pocket Option? Myths vs. Facts breakdown

We decided to dispel some myths, and look squarely at the facts, based on trading principles and realistic ...

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

-

Trade-barrier analytics and their impact on Nigeria’s supply ...

Nigeria’s consumer economy is structurally exposed to global supply chain shocks due to deep import dependence ...

-

A short note on assessing market-creating opportunities

We have researched and determined a practical set of factors that funders can analyse when assessing market-creating ...

-

Rethinking inequality: What if it’s a feature, not a bug?

When the higher levels of a hierarchy enable the flourishing of the lower levels, prosperity expands from the roots ...

-

Are we in a financial bubble?

There are at least four ways to determine when a bubble is building in financial markets.

-

Powering financial inclusion across Africa with real-time digital ...

Nigeria is a leader in real-time digital payments, not only in Africa but globally also.

-

Analysis of NERC draft Net Billing Regulations 2025

The draft regulation represents a significant step towards integrating renewable energy at the distribution level of ...

-

The need for safeguards in using chatbots in education and healthcare

Without deliberate efforts the generative AI race could destabilise the very sectors it seeks to transform.

Most Popular News

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- ChatGPT is now the most-downloaded app – report

- Green economy to surpass $7 trillion in annual value by 2030 – WEF

- Africa needs €240 billion in factoring volumes for SME-led transformation

- CBN licences 82 bureaux de change under revised guidelines