A year in, Nigeria's President might not have long left

Feature Highlight

When narrow interests begin to amass power in Nigeria, the country's various factions tend to realign against them, throwing their weight behind candidates who can restore equilibrium.

Forecast

- As President Muhammadu Buhari continues to lean on his trusted circle of northern political advisers and allies, public frustration over the north's perceived domination of Nigeria's political system will grow.

- The mounting irritation could spur political realignments, including defections from the already strained ruling party to the opposition People's Democratic Party (PDP).

- The PDP's decision to put forth a ticket in the 2019 presidential election featuring candidates from both the north and southeast could split the northern vote, weakening Buhari's support base and threatening his chances for re-election.

Analysis

In 1999, Nigerian strongman Abdulsalami Abubakar agreed to hand over power to civilian leaders, replacing the military rule that had typified much of Nigeria's political history with a rotational power-sharing agreement. The deal, crafted by the ruling party at the time, was intended to prevent any one region or ethnic group from monopolizing influence in the Nigerian government. And indeed, for more than a decade, the country's various administrations were more or less inclusive.

But the untimely death of former President Umaru Yaradua, a northerner from Katsina state, upset the fragile balance in 2010. His demise led to southern Vice President Goodluck Jonathan's rise to prominence, an ascent that northern Nigeria viewed as a usurpation of the power it was owed. When Jonathan then attempted to win a second term — a move that would have extended southern rule by four years — the country's power-sharing system broke down completely, driving a wedge between members of the ruling People's Democratic Party (PDP). Many defected, joining the All Progressives Congress led by northerner and former military ruler Muhammadu Buhari, who went on to win Nigeria's presidential election in 2015.

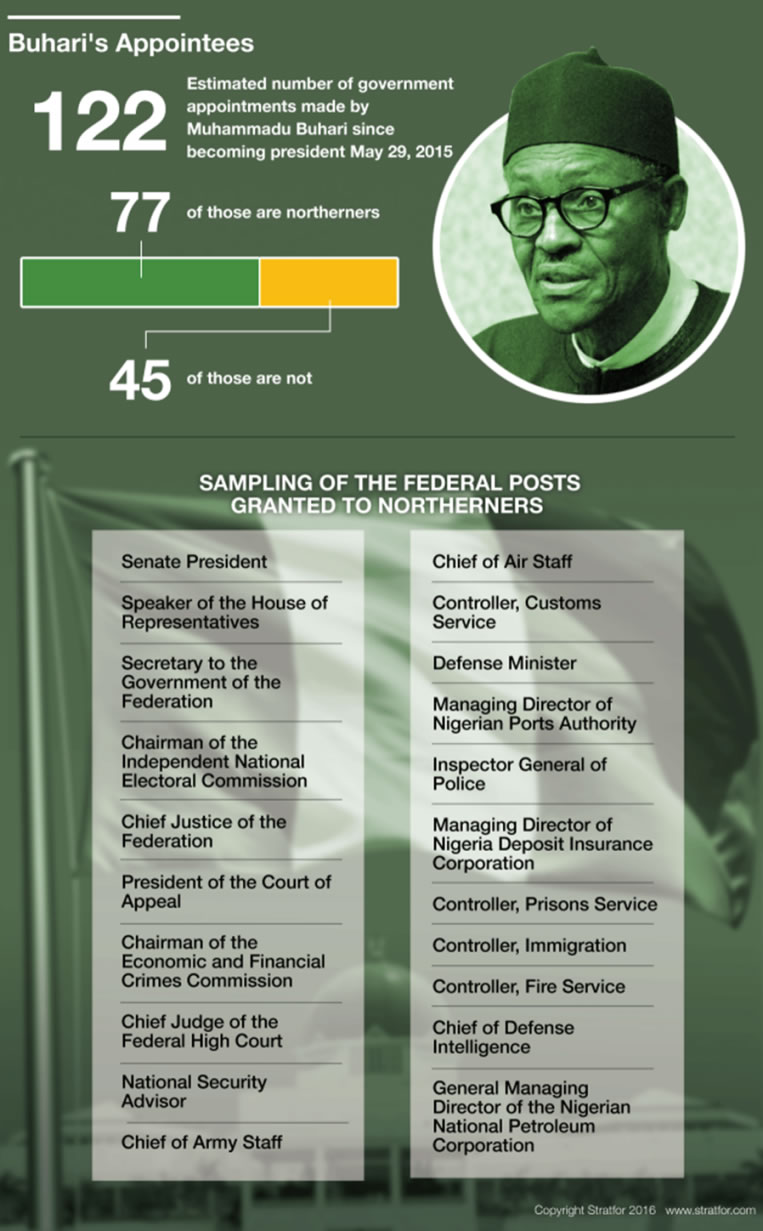

Now people are beginning to fear that Buhari is skewing the balance of power in the opposite direction, concentrating authority in the hands of his northern political constituents and trusted advisers. Some in the south have even warned of the federal government's impending "northernization." But the truth may not be that clear-cut.

The North's Place in Nigerian Security

By law, at least one ministerial or vice ministerial post must be granted to each of Nigeria's 36 states. Once those positions have been filled, the remaining appointments can be made at the president's discretion. Buhari has given many of Nigeria's leftover security portfolios to northern figures — seven of the 10 most important non-ministerial jobs related to security, in fact. The move, unsurprisingly, has irritated some of the country's southerners. Yet Jonathan, a southerner himself, relied just as heavily on northern officials to handle issues of defense. (He, too, appointed northerners to seven of the same 10 security portfolios.) Granted, Jonathan was in a very different position than Buhari is in now. The former's tenure was so controversial that Jonathan may have felt politically unable to appoint a slew of southerners to sensitive security posts without risking severe public backlash.

But the government's dependency on the north is more than just a matter of politics. The region — and specifically, the ethnic Hausa who live there — has a military tradition that dates back generations. Since Nigeria's independence in 1960, northerners have dominated the upper ranks of the armed services, in turn predisposing them to hold an outsize share of high-level security roles. Moreover, the only military conflict Nigeria has had to fight in recent years involves Wilayat al Sudan al Gharbi, an Islamist extremist group better known as Boko Haram that hails from the country's northeast. That Muslim northerners lead the fight against the group is crucial because it enables the government to counter Boko Haram's claims that Christian southerners are heading the charge against it — a message that risks alienating northern Muslims from the military.

In addition to these strategic advantages, Buhari has several other reasons for favouring officials from the north. As a former military ruler whose previous term was cut short by a coup, the president tends to save sensitive security matters for those he can trust. More often than not, that means people who come from the region he considers home. Widespread corruption — a legacy of Jonathan, who gave his ministers enough autonomy to engage in criminal practices with impunity — has also given Buhari cause to pursue tough anti-corruption measures. To this end, he has opened many high-profile corruption cases against former government officials and is reportedly recouping millions of dollars in stolen government funds. He has even named himself the minister of petroleum, likely in an effort to prevent the corruption that has stained the post in the past.

Nevertheless, Buhari's detractors have interpreted the move as an unwillingness to share political power. Similarly, the spate of corruption charges against former civil servants — many of whom are southerners — has been seen as an attempt to punish the previous administration and any potential challengers within it. In reality, though, the anti-corruption drive is more likely aimed at recovering the massive sums of money that were siphoned off over the past four years, particularly since Nigeria's finances are under severe strain.

And so, though Buhari has appointed some southerners to posts including the chief of naval staff, his reputation for northern favouritism has become difficult to shake. Buhari's recent removal of Emmanuel Ibe Kachikwu, a southerner and the minister of state for petroleum resources, from the head of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. probably only reinforced the image. Some in the south saw this as yet another loss of influence, though in all likelihood Kachikwu's role was originally meant to provide temporary oversight of the company's reforms, rather than permanent guidance. Still, that did not stop groups such as the Niger Delta Indigenous Movement for Radical Change from condemning Kachikwu's ouster, nor were they alone in their resentment.

Political Blowback From the South

In fact, the recent uptick in attacks against oil and natural gas infrastructure in the Niger Delta may be caused in part by mounting dissatisfaction with Buhari's tactics. Since January, several militant groups — most notably, the Niger Delta Avengers — have taken to blowing up pipelines, among other things, to draw attention to the southernmost region's long-standing grievances. Chief among them is the unequal distribution of wealth gained from the sale of the Niger Delta's oil. One possible explanation for the rising violence is that certain factions are attempting to address the loss, whether real or imagined, of the political power that they secured under Jonathan's administration. Either way, the government's inability to redress the restive region's gripes by providing greater resources has reinforced the narrative that Buhari's government simply does not care about southern issues.

This explains why, after Buhari declared amid the string of attacks that Nigeria's unity is "nonnegotiable," several southern groups and figures rebuked his statement, calling for more autonomy for individual states. Obong Victor Attah, the former governor of the southern state of Akwa Ibom, has even put forth a proposal for greater fiscal federalism that would essentially allow states to lay claim to a bigger share of the profits they produce. According to Attah, passing the measure would restore faith in Nigeria's political system. Though the debate over Nigerian unity has not yet reached an alarming level, the grumblings of important figures such as Attah underscore the sense of injustice pervading the region.

If left unchecked, popular frustration could eventually have political consequences for the president. When narrow interests begin to amass power in Nigeria, the country's various factions tend to realign against them, throwing their weight behind candidates who can restore equilibrium. That is how Jonathan's campaign for re-election was defeated in 2015, and if Buhari is not careful, it could be how his is thwarted in 2019.

Of course, Buhari still has three years left in his term — plenty of time to change course if anxiety over the "northernization" of the government begins to significantly threaten his popularity. But the fact remains that the public's perception, along with the many other problems Nigeria faces, could erode support for the overburdened ruling party, especially since Nigerian political alliances are by nature quite fluid.

Buhari's All Progressives Congress is already divided between two factions: its original members, and former PDP figures who broke ranks with Jonathan after he sought a second term. If Buhari's rule becomes more contested, the latter could return to their old party, leaving the president's coalition all the weaker. Their defection may be made even more likely by the PDP's recent announcement that it intends to choose a northern presidential candidate and a vice presidential candidate from the southeast to represent it in the next race. A joint ticket could be enticing to former PDP members, most of whom are from the north, as well as any ruling party members who have been marginalized under Buhari's reign. More important, the selection of a northerner to lead the ticket would probably split the northern vote, severely undermining Buhari's electoral base as he fails to broaden his constituency southward.

The president has time to adjust his image. Whether he has the will to do so is another matter. But one thing is clear: If Buhari chooses to ignore the south's growing concerns, he will have to accept the fact that he may not be president for much longer.

Stephen Rakowski is a Sub-Saharan Africa Analyst at Stratfor, where he monitors political, security and economic trends unfolding across the continent. "A year in, Nigeria's President might not have long left" is republished with the permission of Stratfor and under content confederation between Financial Nigeria and Stratfor.

Source: https://www.stratfor.com/analysis/year-nigerias-president-might-not-have-long-left

Other Features

-

Expect turbulent asset markets in 2026

The negative impact of Trump’s tariff and immigration policies will be felt more acutely in 2026.

-

The scars of partition

Contrary to his rosy assurances, partitions often result in tragedy, as borders drawn by cartographers rarely align ...

-

Best site to sell Bitcoin in Nigeria (Fast BTC to Naira in 2026)

Apexpay stands out because it focuses on what Nigerian users actually want: speed, good rates, and simplicity.

-

The quiet influence of securitisation in financing Africa's energy ...

The scale of Africa’s energy transition demands financial solutions that are modern, secure, and scalable.

-

Lean carbon, just power

Why a small, temporary rise in African carbon emissions is justified to reach the continent’s urgent ...

-

Utilising the FTSA to unlock value in Nigeria’s gas production

Given the FG’s recent investment drive to fully monetise the country’s gas reserves, now is an opportune ...

-

Islamic finance posts double-digit growth in 2025

Forward-looking projections suggest that total assets are on track to cross USD 6 trillion by the end of 2026.

-

Can you earn consistently on Pocket Option? Myths vs. Facts breakdown

We decided to dispel some myths, and look squarely at the facts, based on trading principles and realistic ...

-

How much is a $100 Steam Gift Card in naira today?

2026 Complete Guide to Steam Card Rates, Best Platforms, and How to Sell Safely in Nigeria.

Most Popular News

- Pan-African nonprofit appoints Newman as Advisory and Executive Boards Chair

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- Abebe Aemro Selassie to retire as Director of African Department at IMF

- Dollar slumps as Fed independence comes under fire

- UN adopts new consumer product safety principles