Greece and the looming German-French divide

Summary

Germany wants to prevent the European Union from becoming a transfer union, in which northern countries permanently subsidize the south.

Summary

French leaders took an active role in negotiations in the weeks leading up to Greece's agreement with its creditors because of a combination of long-term and short-term concerns. France is both a Mediterranean and a Northern European country, and as such is interested in preserving its role as a middleman between Germany and the eurozone periphery. Paris is also worried about the economic and political consequences of a potential "Grexit," particularly the destabilization of the Eastern Mediterranean region and the risk of the crisis spreading to the fragile economies of Southern Europe.

Germany's hardline strategy during the negotiations with Greece created the potential for future conflict between Paris and Berlin, especially because resistance to austerity and, in some cases, EU integration is growing in Mediterranean Europe. More countries will likely resist German leadership in the future, making it more difficult for France to preserve its role as mediator between Northern and Southern Europe. In addition, political developments in France could increase resistance to Germany's leadership of the European Union.

Analysis

Germany adopted the negotiating stance it did with Greece because of its political and economic needs. As the largest economy in Europe, Germany wants to prevent the European Union from becoming a transfer union, in which northern countries permanently subsidize the south. This explains Germany's reluctance to accept Greece's requests for debt forgiveness and its insistence that no eurozone member can default on its debt and remain in the currency union.

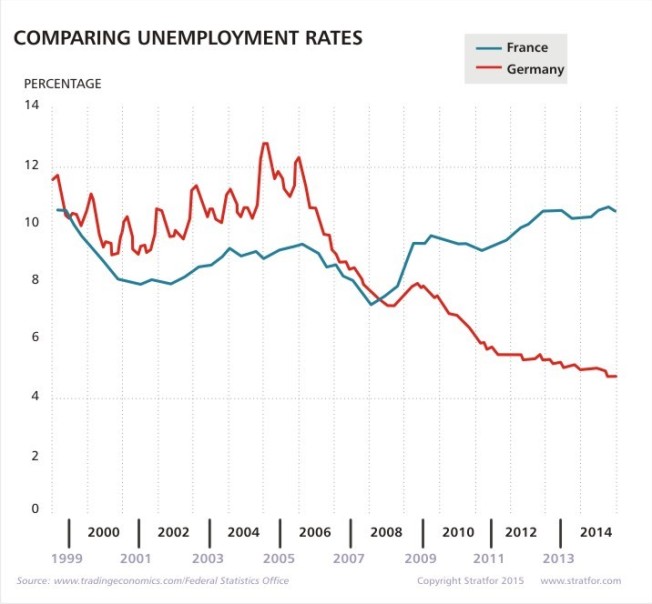

There is also a domestic component to Berlin's behavior: During the past decade, the German government constructed a narrative that blames southern nations for the shortcomings of the eurozone and contrasts German productivity to Mediterranean inefficiency. As the Greek crisis escalated, this narrative limited Berlin's room for action, and German Chancellor Angela Merkel was forced to secure a deal with Athens that her own parliament and conservative voters could accept.

But German strategists found unexpected resistance in France. During the early stages of the crisis, the French government remained relatively silent in an effort to protect its ties with Germany, which are the foundation of the European Union and a key element for peace in Europe. But as the crisis escalated, Paris changed its strategy. French officials helped their Greek counterparts come up with enhanced proposals for economic reforms, and French President Francois Hollande became the strongest supporter of a deal during the marathon negotiations in Brussels.

France's behavior irritated the Germans. After helping the Greeks draft their proposals, the French discovered that Germany was actually considering temporarily suspending Greece's membership in the eurozone. Nevertheless, negotiators finally came to an agreement that on the surface benefits both the Germans and the French. The Germans were satisfied because Athens was asked to introduce deep reforms before receiving any fresh money. France saved face because it was able to help avoid a Grexit and to demonstrate its role as a key political player in Europe. However, the deal has set a dangerous precedent for Europe.

France's Place in Europe

France's geographic position in Europe explains its evolving strategy during the debt negotiations. The European Union was designed as an alliance between Germany and France that would bring peace and prosperity to Europe. In its original form, it was meant to bring together Germany's economic might and France's political and military power. Its goal was to integrate postwar Germany into a broad European alliance under French leadership.

But several things have changed in the past six decades. First, the European Union's evolution from a club of six countries in Central and Western Europe to a bloc of 28 nations stretching from the Scandinavian Peninsula to the Black Sea changed the configuration of power and influence in Europe. This coincided with a push to consolidate a hefty institutional structure to impose a common set of rules on fiscal responsibility and supranational governance. Moreover, Germany's reunification consolidated its role as the largest and most populated economy on the Continent, while the euro was created as a common currency that would force Germany, France and the rest of the European Union into a permanent quest for consensus.

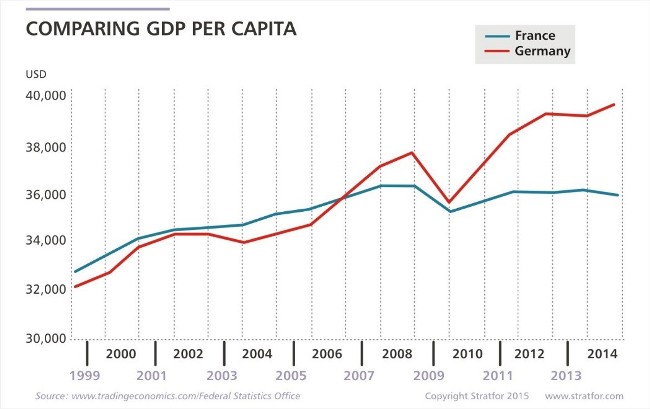

More recently, the economic crisis weakened the French economy and, as a result, France's political influence. Meanwhile, it enhanced Germany's role as the main decision-maker in Europe. France is still the main military force in continental Europe and has been particularly active abroad in recent years, as exemplified by its interventions in Northern and Central Africa. But Paris is concerned about its weakened political influence in EU affairs. Today, many of the most important decisions in Europe are made in Brussels, Berlin and Frankfurt.

These changing dynamics were clear during the Eurogroup negotiations on the Greek crisis. Berlin won the backing of fellow Central and Northern European nations, including the Netherlands, Finland, Slovakia and the Baltic states, most of which are part of Germany's supply chain and all of which have strong trade ties with the Germans. But for historical reasons, Germany is a reluctant hegemon. Berlin does not want to be perceived as using its supremacy unilaterally, and it needs to secure as much consensus as possible in its leadership of the European Union. In many cases, this means accommodating Paris.

Unlike Germany, France is both a northern and a southern European power. Paris needs to consolidate a sphere of influence in the Mediterranean as a counterweight to Berlin. The Eastern Mediterranean region is already in flux, with a civil war in Syria, political tension in Turkey and a failed state in Libya. Greece is also an entry point for asylum seekers and migrants, some of whom could be linked to terrorism. France fears that a chaotic and impoverished Greece could lead to growing instability in the region – a view that is shared by Italy, another Mediterranean power. In addition, Paris fears that a Grexit would produce a domino effect ending the common currency and, in the process, severing the political and institutional ties that bind Germany to France.

Paris' push for a deal with Athens was also affected by many short-term calculations. Several lawmakers from France's Socialist Party government pressured Hollande to more actively help the Syriza administration in Athens. Paris also worried that a Grexit could have led to damaging economic and financial repercussions for France's fragile economic recovery, less than two years before the next French presidential election. Beyond these immediate concerns, though, French reasoning was guided primarily by the need to enhance its role as a bridge between southern and northern Europe.

The Coming Crisis

For now, Germany's hard-line strategy has worked. Merkel's popularity is strong at home, while Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaueble was praised by local media for defending Germany's interests. In the long term, however, the strategy is dangerous because it showed a particularly unpleasant side of Germany's leadership of the European Union. With euroskeptic and anti-austerity sentiments on the rise in countries such as Spain, Italy and Portugal, in the coming months and years Berlin will likely have to deal with other countries demanding a change of direction in the eurozone.

Berlin should also expect more problems with Paris. France and Germany have different views about the role and function of the European Union. France wants a political alliance in which deficit and debt rules are flexible, some inflation is tolerated in order to create jobs, and some degree of protectionism is accepted to protect local economies. Germany, on the other hand, believes that only fiscal responsibility and low tolerance for infractions of EU rules will prevent a new crisis.

These visions have repeatedly clashed since the beginning of the European crisis and will continue to, potentially more often, because of the current political trends in Europe. Many of the burgeoning crises in Europe (as well as the main political movements that push for a change of direction) will originate in Mediterranean countries. This will put France in an increasingly difficult position, as Paris will struggle to maintain good ties with Berlin when representing the interests of Southern Europe. Additionally, political developments in France will lead to conflict with Germany, especially if a slightly euroskeptic center-right candidate and one from the nationalist right end up as the main contenders in the French presidential election in 2017, as seems likely.

A point could be made that Greece is a small economy and Germany would have behaved differently if it were dealing with Italy or Spain. Larger eurozone economies may think they are too big to fall and would have a better chance in negotiations. However, they could also think that the crisis has proven that the transfer union will never materialize, that membership in the eurozone is not as "irreversible" as EU leaders say, and that now is the time to protect their own economies. This could mean several things for Mediterranean nations, from proposing the reinstitution of trade barriers to leaving the currency union altogether. Ultimately, it does not matter that Germany never made good on its threats to expel Greece from the eurozone. The Greek deal delayed the chaos a Grexit would have caused, but it has led to debate about the irrevocability of EU integration, which may very well be just as dangerous for the European project.

“Greece and the Looming German-French Divide ” is republished with permission of Stratfor and under content confederation between Financial Nigeria magazine and Stratfor.

Related

-

I am a migrant

In 2014, Syrians accounted for 26% of the new foreign businesses registered in Turkey.

-

Nigeria records $87 billion in trade misinvoicing in 10 years

Trade misinvoicing is a major type of illicit financial flow and can be used to evade customs duties, VAT taxes, and ...

-

Nigeria and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund

The IOPC funds represent not just an international obligation, but a lifeline for nations that live with the daily risk of ...