Why India is an obstacle to its own success

Feature Highlight

Global influence is nearly impossible to achieve without a strong economy.

Forecast

- India's inability to push through economic reforms will delay its rise as a global power.

- In pursuit of closer relationships with other countries, Prime Minister Narendra Modi will gradually shift away from India's historical policy of nonalignment.

- But the cultural legacy of that strategy will remain entrenched in India's foreign policy establishment, slowing the pace at which India and the United States deepen their defence ties.

Analysis

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi wants nothing more than for his country to take on a bigger role in international politics. Since assuming office in 2014, he has travelled to 54 countries across six continents. In the past eight weeks alone, he has attended summits with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, East Asian countries, G-20 members and the BRICS states. Yet for all of the diplomatic bustle, India's aspirations of becoming a great power likely will go unrealized as a lagging economy and a tradition of avoiding foreign alliances continue to restrict New Delhi's movements abroad.

Uneven Economic Progress

Global influence is nearly impossible to achieve without a strong economy. If a country enjoys high standards of living, its government does not need to devote much of its budget to subsidies and social services. Moreover, economic growth yields greater tax revenue, which can be put toward military spending without sacrificing developmental funds.

The Indian economy's performance has been, in many ways, impressive of late. Between 1950 and 1980, the country's gross domestic product grew by an average of 3.5 percent per year as its population expanded by 2.5 percent per year, meaning that real incomes rose by only 1 percent annually. Since 1980, however, that figure has shot up to 4 percent, boosting the government's tax revenue tenfold between 1995 and 2013. Yet because the quality of this growth has been uneven, India remains a poor country with the lowest GDP per capita of the G-20 states.

It is no surprise, then, that attracting foreign investment to fuel economic growth has become a key component of Modi's foreign policy. And so far, he has had some success: Last year, a record $44 billion in foreign direct investment flowed into India. Even so, most of that was funnelled into India's already robust services sector; only 6 percent went to its budding manufacturing industry.

This proved frustrating for Modi, who had launched the "Make in India" campaign a year prior with the express purpose of boosting manufacturing's share of the economy to a quarter of the country's GDP. But without completing the land, labour and tax reforms needed to make way for a manufacturing base and a large semiskilled labour pool, India will continue to have difficulty achieving the growth it so desires. Pushing such reforms through, however, would first require Modi's party to increase its representation in parliament by sweeping state elections in 2017. Unless that happens, any new measures will likely continue to remain stalled, undercutting the manufacturing sector's prospects for external financing – and Modi's aspirations for economic growth.

A History of Avoiding Entanglement

The economy will not be the only force working against India's ambitions to improve its global status. After gaining its independence in 1947, India fought to preserve its hard-won sovereignty as the Cold War dawned by adhering to the mantra of "swadeshi," or self-sufficiency, advocated by the country's first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. Imbibing this ideal in his vision for India, Nehru constructed a socialist economy in the Soviet style and adopted a worldview that aligned with Moscow's. (At the same time, Washington cultivated ties with India's upstart regional rival, Pakistan.) But despite his shared interests with the Soviet Union, Nehru wanted to ensure that India gained an independent role abroad commensurate with its 5,000-year history as a mighty civilization. He thus adopted a policy of nonalignment, eschewing alliances with other nations in an effort to discourage colonialism while remaining relevant in global politics. New Delhi has honoured that policy ever since, despite the fact that it is often at odds with India's need to make pacts with foreign partners.

In 1991, a balance-of-payments crisis forced India to ask the International Monetary Fund for an emergency loan. The organization agreed, on the condition that New Delhi dismantle the License Raj, an elaborate system of licensing and red tape regulating the operation of Indian businesses. After it did, Indian growth jumped to 6.5 percent, and its trade-to-GDP ratio reached 43 percent by 2013, up from 14 percent in 1995. As India's long-closed economy began to open to the rest of the world, its politics followed. In the wake of the Soviet Union's collapse, the only major power left to seek capital and technology from was the United States, and India began its slow tilt toward the West.

Old Habits Die Hard

Twenty-five years later, Modi appears to be interested in cultivating that relationship. New Delhi is counting on Washington's support as it tries to increase its prominence in international institutions, including by gaining a permanent seat on the U.N. Security Council and in the Nuclear Suppliers Group. Building a defence relationship with the United States will be crucial to winning the backing of Washington, which views India as a bulwark against Chinese expansionism in South Asia. But strengthening its U.S. ties will be difficult for India as long as Nehru's legacy still endures.

Modi has made deepening India's partnership with the United States a priority all the same. In January 2015, he invited U.S. President Barack Obama to be the chief guest at India's Republic Day parade, the first time the honour had been bestowed on a U.S. president. Modi also accepted an invitation to address the U.S. Congress in June 2016. After several more high-level exchanges, India agreed to sign a logistics and support agreement with the United States, one of three defence deals that would allow the two countries to refuel at one another's military bases. Considering that the deal was first broached a decade earlier — and that in the interval before it was finalized, Indian administrations from both sides of the political spectrum came and went — it seems unlikely that New Delhi's reluctance to forsake its nonalignment strategy is a partisan matter, or one liable to disappear any time soon.

India's refusal to enter into alliances does not mean that its interpretation of Nehru's policy will endure. Modi, for instance, has never used the term "nonalignment" in his speeches, and in August, Indian Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar said that "blocs and alliances are less relevant today." The following month, Modi chose not to attend a Non-Aligned Movement summit, a venue India had long used to position itself at the forefront of the world's developing nations. Instead, the country has found another means of achieving the same goal: advocating climate justice, or the idea that developing countries should not have to restrict their use of fossil fuels to make up for pollution perpetrated by industrialized states.

Half a century after his rule, Nehru's influence is still palpable in Indian foreign policy circles. But his strictures on the formation of close ties with larger powers are beginning to soften, bit by bit, as India forges ahead in its quest for a leading role on the international stage.

“Why India Is an Obstacle to Its Own Success” is republished with the permission of Stratfor, under content confederation between Financial Nigeria and Stratfor.

Other Features

-

The best sites to buy and sell Bitcoin in Nigeria: A comprehensive ...

Buying and selling BTC doesn’t have to be a hassle. Check out to best sites to buy and sell Bitcoin in Nigeria ...

-

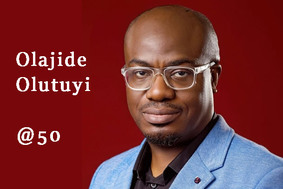

At 50, Olajide Olutuyi vows to intensify focus on social impact

Like Canadian Frank Stronach utilised his Canadian nationality to leverage opportunities in his home country of ...

-

Reflection on ECOWAS Parliament, expectations for the 6th Legislature

The 6th ECOWAS Legislature must sustain the initiated dialogue and sensitisation effort for the Direct Universal ...

-

The $3bn private credit opportunity in Africa

In 2021/2022, domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP stood at less than 36% in sub-Saharan ...

-

Tinubunomics: Is the tail wagging the dog?

Why long-term vision should drive policy actions in the short term to achieve a sustainable Nigerian economic ...

-

Living in fear and want

Nigerians are being battered by security and economic headwinds. What can be done about it?

-

Analysis of the key provisions of the NERC Multi-Year Tariff Order ...

With the MYTO 2024, we can infer that the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry is at a turning point with the ...

-

Volcanic explosion of an uncommon agenda for development

Olisa Agbakoba advises the 10th National Assembly on how it can deliver on a transformative legislative agenda for ...

-

Nigeria and the world in 2024

Will it get better or worse for the world that has settled for crises?

Most Popular News

- IFC, partners back Indorama in Nigeria with $1.25 billion for fertiliser export

- NDFF 2024 Conference to boost Nigeria’s blue and green economies

- CBN increases capital requirements of banks, gives 24 months for compliance

- CBN settles backlog of foreign exchange obligations

- Univercells signs MoU with FG on biopharmaceutical development in Nigeria

- Ali Pate to deliver keynote speech at NDFF 2024 Conference