There's no easy way out of Africa for French forces

Feature Highlight

The weakness of Sahel states, including Mali and Niger, will continue to force them to rely on foreign powers, such as France, for security.

Forecast Highlights

• The weakness of Sahel states, including Mali and Niger, will continue to force them to rely on foreign powers, such as France, for security.

• France will continue working to prevent a security crisis from developing in any of its partner states in the terrorist-rich Sahel.

• Newly elected French president Manuel Macron will be limited in his ability to militarily disengage from Mali and Africa more broadly.

Despite all of France's pressing domestic issues, its newly elected president, Emmanuel Macron, travelled to Mali during his first week in office, sending a clear message to the world: France still considers Africa a top priority.

On the trip, Macron met May 19 with Malian President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita and with some of the more than 3,000 French troops stationed in the country under the aegis of Operation Barkhane. Though Macron's political strategy is still solidifying from campaign promises into actual policy, his administration will face the same severe constraints in the Sahel region as did his predecessors, including institutional weakness, resilient Islamic militant groups and rough physical terrain – which will make a military drawdown difficult.

New President, Old Problems

There is little doubt that France's 2013 intervention helped stave off a complete collapse of the Malian state. The French military Operation Serval, begun in January 2013, had four goals: The first was assisting Malian and African forces to halt the advance of extremists and reinstating Malian sovereignty over the breakaway north. The second was striking terrorist harbours to disrupt operations. The third was protecting the country's capital, Bamako (at the country's centre). Finally, it was to set the conditions for a United Nations mission in the country, a European Union Training Mission (EUTM), and free and fair elections by July 2013.

As originally envisioned, once Operation Serval had met those goals, France would be able to hand off security operations to the U.N. mission, MINUSMA. But for a variety of reasons, that did not happen, and France instead has had to dig in for a longer-term mission.

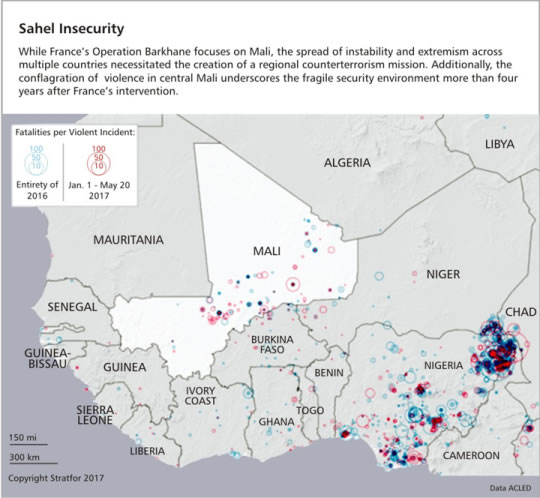

Against the resiliency of militant groups operating in Mali and in the broader region, MINUSMA has largely proved inadequate and has quickly become the United Nations' most fatally dangerous mission. To underscore the poor security situation in the country, on May 17, the new head of U.N. peacekeeping announced that a rapid intervention force was being sent to the centre of the country. Though details about the size and scope of the force remain unclear, the decision to deploy it was undoubtedly prompted by the noticeable uptick in militant attacks and in inter-communal violence in the area in recent years. Those are problems that the Malian military has had difficulty effectively addressing because of enduring political instability and economic weakness.

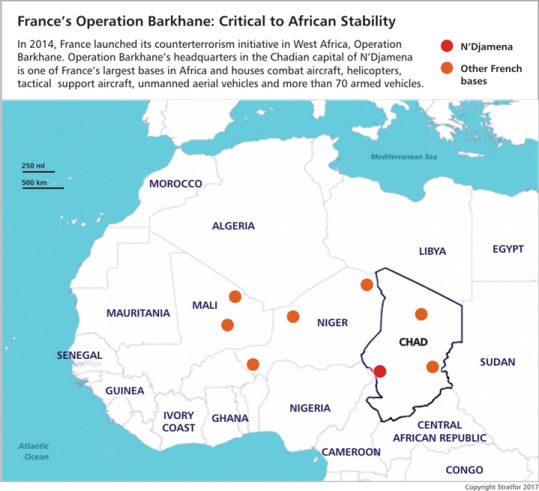

Recognizing the fragility of the Sahel region, France, too, broadened Operation Serval in 2014 into a regional counterterrorism strategy, known as Operation Barkhane. Many countries in the Sahel region – including Niger, Burkina Faso, Chad and Mauritania – are threatened to various degrees by state weakness and transnational militancy. Even after years of being targeted, al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al Mourabitoun, the Macina Liberation Front, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahel and other Islamist militant groups remain active and capable of attacks against soft targets and international forces in the region. However, in the absence of the extreme power vacuum that allowed for their rapid territorial gains in 2012 and 2013, they have been held back somewhat.

Planners under former French President Francois Hollande determined that a stronger and more militarized strategy in the Sahel was necessary to hold the region together. The 2013 edition of the French white paper on defence and national security – a document explaining the intentions of France's defence policy – clearly stated the new approach. According to the document, to ensure regional stability, there would be a greater push for utilizing French special forces and technology, a permanent deployment of army and naval assets to the continent, and more cooperation with local African forces. The plan was a significant departure from that of Hollande's predecessor, Nicolas Sarkozy, who pushed for reduced military involvement in Africa in favour of stronger economic engagement.

Revisiting Strategies

With Macron's presidential victory, France's relationship with Mali and with the broader Sahel region could be changing again. Macron stated during his campaign that although the 2013 French intervention into Mali was justified, it also undermined Sarkozy's attempts to normalize relations with former French colonies. According to Macron, France must capitalize on the security gains it has made in Mali and must broaden its Africa mission with an all-encompassing economic strategy. In essence, the debate is whether to focus on combating the immediate concern of terrorism militarily or to focus on fighting the long-term drivers of instability, including endemic poverty and institutional weakness, through economic engagement.

But though Macron could implement a more economically focused Africa strategy, he will be limited in how far he can draw down militarily in the region. Many countries in the Sahel, including Mali and Niger, are woefully unprepared to deal with the transnational terrorist threat emanating from within and beyond their borders and would completely succumb to it without international help. Moreover, any military drawdown would reduce France's ability to act in the case of emergency and to project its power in Africa. France's military prowess steadily declined because of decades of budget cuts, and pulling forces out of Africa would weaken it even further by reducing the country's importance on the international stage.

Relatedly, though the United States has refrained from contributing troops to the Sahel struggle, it has provided France with critically important assistance in the realms of intelligence sharing, aerial refuelling, transportation and other support areas that have helped underpin France's ambitious regional counterterrorism strategy. The administration of U.S. President Donald Trump has expressed comfort with the arrangement, meaning that it will continue despite uncertainties about White House foreign policy aims elsewhere.

No matter Macron's intentions, he will soon realize that stability in the Sahel is largely dependent on France's counterterrorism operations. Thus, though African nations may welcome an emphasis on economic development, that development is unlikely to replace military intervention.

“There's No Easy Way Out of Africa for French Forces” is republished with thepermission of Stratfor, under content confederation between Financial Nigeria and Stratfor.

Other Features

-

The best sites to buy and sell Bitcoin in Nigeria: A comprehensive ...

Buying and selling BTC doesn’t have to be a hassle. Check out to best sites to buy and sell Bitcoin in Nigeria ...

-

At 50, Olajide Olutuyi vows to intensify focus on social impact

Like Canadian Frank Stronach utilised his Canadian nationality to leverage opportunities in his home country of ...

-

Reflection on ECOWAS Parliament, expectations for the 6th Legislature

The 6th ECOWAS Legislature must sustain the initiated dialogue and sensitisation effort for the Direct Universal ...

-

The $3bn private credit opportunity in Africa

In 2021/2022, domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP stood at less than 36% in sub-Saharan ...

-

Tinubunomics: Is the tail wagging the dog?

Why long-term vision should drive policy actions in the short term to achieve a sustainable Nigerian economic ...

-

Living in fear and want

Nigerians are being battered by security and economic headwinds. What can be done about it?

-

Analysis of the key provisions of the NERC Multi-Year Tariff Order ...

With the MYTO 2024, we can infer that the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry is at a turning point with the ...

-

Volcanic explosion of an uncommon agenda for development

Olisa Agbakoba advises the 10th National Assembly on how it can deliver on a transformative legislative agenda for ...

-

Nigeria and the world in 2024

Will it get better or worse for the world that has settled for crises?

Most Popular News

- IFC, partners back Indorama in Nigeria with $1.25 billion for fertiliser export

- CBN increases capital requirements of banks, gives 24 months for compliance

- CBN settles backlog of foreign exchange obligations

- NDFF 2024 Conference to boost Nigeria’s blue and green economies

- Univercells signs MoU with FG on biopharmaceutical development in Nigeria

- Ali Pate to deliver keynote speech at NDFF 2024 Conference