Martins Hile, Editor, Financial Nigeria magazine

Follow Martins Hile

![]() @martinshile

@martinshile

Subjects of Interest

- Governance

- SMEs

- Social Development

Implications of Nigeria's moribund reading culture 14 Jun 2018

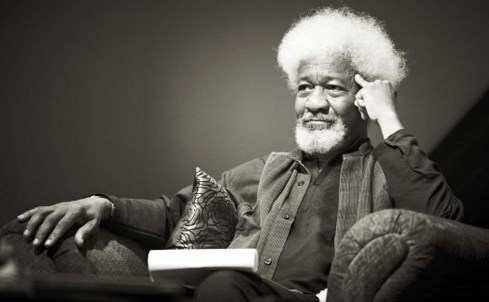

Nigerian literary icon, Wole Soyinka

Over 75 million Nigerians are illiterate. A substantial number of those who can both read and write are subliterate – in other words, they have a low level of literacy or are not interested in literature, as represented by any body of written works.

“Reading and writing is a culture," Jide Akintunde echoed during our recent Editorial Board meeting when the discussion segued into Nigeria's poor reading culture. Despite it being a popular subject of discussion among the Nigerian literati over the last three decades, nothing significant has happened to improve reading and writing as a sociocultural practice.

Part of the fallout include underperformance in education. For instance, the results of West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) for private candidates in both 2017 and 2018 are ingredients for a meal of sober reflection on the state of the nation. Only 26.0% and 17.13% of the candidates in 2017 and 2018, respectively, passed with credits in five subjects, including Mathematics and English Language.

Adult literacy rate data provided in the Human Development Report 2016 is also instructive. The percentage of the Nigerian population (15 years and older) that can both read and write simple statements in everyday life is 59.6%. Comparing this to Cameroon (75%), Ghana (76.6%), Zimbabwe (86.5), South Africa (94.3%), and Equatorial Guinea (95.3), shows Nigeria needs a lot of work to improve literacy achievement.

While writing for the Newyorker, Nigerian novelist, Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani, narrated a conversation she had with the CEO and Managing Director of Bookcraft, Bankole Olayebi, in which the publisher said his company was selling pretty much similar number of books in 2015 that it sold in 1988. This is much worse than stagnation. It suggests 50% fall in the reading public over a period of 27 years, given that the country's population had doubled from 90 million in 1988 to 180 million in 2015.

This has serious implications. Studies have shown there is an almost symbiotic relationship between reading and intelligence. Fluid intelligence comes with the ability to understand things and solve problems. Emotional intelligence, also enhanced by reading regularly, helps with self-awareness, empathy, social skills and managing relationships more effectively.

Reading also provides a therapeutic effect, while also slowing mental decline. Gorging on literature for this purpose is an ancient practice called bibliotherapy. Thus, the relationship between reading, knowledge acquisition, intelligence and personal empowerment is crucial for economic and societal development. Absent that, and a critical mode of thinking and human development is lost.

In a 1991 article for the now-defunct Los Angeles Times Magazine, Professor of Journalism and Mass Communication at New York University, Mitchell Stephens, asked polemically, "Will a nation that stops reading eventually stop thinking?" It's unfortunate that many of our leaders and role models are not known to be readers or writers. A study conducted in 2004 shows that the average Nigerian reads less than one book in a year. Only one percent of successful men and women in the country reportedly read at least one non-fiction book in a month. Perhaps, this could explain why Nigeria is yet to have a transformational commander-in-chief because, despite the cliché, all good leaders are readers.

The downturn in reading and book readership actually has a global dimension, especially given the onslaught of the digital revolution. But there are divergent opinions on the subject. Commentators who argue that books – whether in paper or electronic format – are dead are met with opposing arguments, suggesting that although the means of their delivery might have been diversified, books are being read across platforms.

According to the NPD BookScan, a service that tracks the preponderance of print sales, 687.2 million total units were sold last year, up from 674.1 million in 2016. Book sales have actually risen 10.8% between 2013 and 2017. But suffice to say that much of this is a reflection of the entrenched practice and culture of writing and reading in developed societies.

The culture of reading has to be created in children from a very young age. A rich environment that fosters a habit of reading starts at home before a child proceeds to school. More books should be bought for children than smartphones and tablets. Nigerian homes need to be fitted with more bookshelves and bookcases than flat screen TVs and laptops.

While it is imperative for federal and state governments to increase funding in education – by declaring a state-of-emergency in the sector – the private and social sectors need to collaborate on initiatives to promote a strong reading culture in the country. We need an effective campaign to bring back the libraries to our schools and communities. Reducing environmental noise, which is inimical to reading, must be a policy imperative.

Private organisations that are falling over themselves to sponsor the Big Brother reality show, singing competitions, and inane sitcoms should endeavour to express their corporate social responsibility by sponsoring campaigns to revive a reading culture in communities where they operate.

Writers and publishers must be undaunted. An editorial partner of Financial Nigeria recently broached the idea of changing the delivery of its editorials from purely textual to incorporate infographics. The rationale – which partly informed the subject of my June editorial – was the need to have graphic visual representations of information because people are too busy nowadays to read lengthy texts.

If the reading culture is on an irretrievable decline, the writing profession and the publishing industry is at great risk. Why should anyone write a book or an essay when nobody will read it? The decline or demise of the publishing industry is not without long-term implications for the enlightenment of society and human capital development in the country.

Martins Hile is the Executive Editor, Financial Nigeria magazine

Latest Blogs By Martins Hile

- Social outcomes as the tail that wags climate action

- Lessons for Nigeria's climate finance strategy

- Rethinking Nigeria's development for people-centred outcomes

- Nigeria's economic prospects in a changing world order

- Naira commoditisation as CBN's cashless policy flaw