Ebola response masks Nigeria’s low health governance capacity

Summary

Nigeria has struggled, both before and after the Ebola epidemic, to combat Lassa fever.

In this exclusive interview, Darrell M. West, Vice President of Governance Studies and Director of the Center for Technology Innovation at the Brookings Institution, spoke to Jide Akintunde, Managing Editor, Financial Nigeria, on the new study that places Nigeria at the bottom of the ranking of 18 low- and middle-income African and Asian countries, on health sector governance capacity.

Jide Akintunde (JA): The ranking of Nigeria in your new report -- Health Governance Capacity: Enhancing Private Sector Investment in Global Health – is startling. The country ranks at the bottom, well below Liberia and Sierra Leone – two of the three West African countries whose health systems collapsed during the Ebola pandemic of 2013 – 2016, while Nigeria was resilient. What is missing in Nigeria’s health governance capacity that explains the country’s dismal ranking?

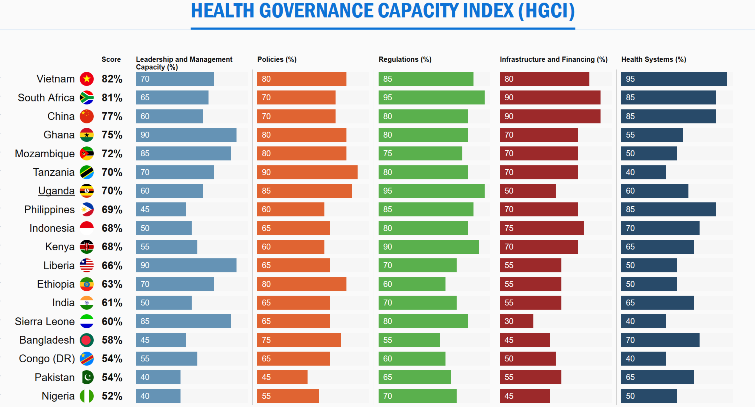

Darrell M. West (DMW): The Health Governance Capacity Index (HGCI) examines each country’s policy, legal, and regulatory frameworks. In the case of Nigeria, the low overall score was the result of a combination of factors. For example, in the “Leadership and management capacity” dimension of the HGCI, which includes indicators related to issues such as corruption, political stability, and foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP, Nigeria scored only an 8 out of 20 points. In the “Health systems” dimension of the HGCI, which includes measures such as infant mortality rate, life expectancy at birth, and population at risk of malaria, Nigeria also received low scores. Those factors, among others, limit the ability to efficiently address health issues and have the kind of governance system that builds public confidence.

Nigeria was rightly praised for its response to Ebola, in particular in relation to successfully averting what could have been a catastrophic outcome if Ebola had spread widely in Lagos. However, there are several factors that suggest that the Ebola response, while commendable, was less representative of a broader underlying national capacity than might initially be suggested. For example, Nigeria has struggled, both before and after the Ebola epidemic, to combat Lassa fever.

Nigeria has important strengths in human capital and natural resources. Those strengths, if properly harnessed, can position the country for better performance in the long-run if it can improve basic governance.

JA: What are the major highlights of the report?

DMW: Our report on health governance capacity reviews performance on many indicators and makes policy recommendations for improving health governance capacity in the 18 countries included in our study. We argue that good governance is a foundational condition for private sector investment in healthcare. Investors who believe their financial resources will reach intended recipients and improve the lives of ordinary people will be more likely to contribute money. Countries that improve governance and build their health infrastructure will be in a strong position down the road to deliver quality healthcare to its residents.

JA: Why does healthcare governance matter for attracting private sector investment – domestic or foreign?

DMW: High quality health governance matters for attracting private investment. Recent studies demonstrate that private investors invest their capital when they see a higher likelihood of a positive return on their investment. Governance is one of the factors that condition private investment in healthcare.

JA: What separate short- and long-term reform recommendations would you make specifically for Nigeria and the other countries that rank close to Nigeria at the bottom of the Health Governance Capacity Index?

DMW: The most important things Nigeria and other nations can do are to improve institutional performance, upgrade their health infrastructure, and increase transparency in the political system. Currently, it can sometimes be hard to see how decisions get made or the way the health system operates. This can discourage outside investors from putting new resources into the country and working to improve healthcare.

JA: Funding healthcare system reform in a lot of the SSA countries will prove more daunting now, given the plunge in the prices of commodities compared to recent historical highs and because of the low appetite for foreign development assistance by the administration of President Donald Trump. Do you share this concern?

DMW: International aid through U.S. foreign assistance, Net Official Development Assistance, Development Assistance for Health, and other channels are crucial for international stability and continued reductions in the global burden of disease. Beyond the humanitarian argument, which we strongly believe, that we have a shared interest in addressing global health concerns, we also believe that it makes economic sense to invest in global human capital through international aid.

As for recent drops in commodities prices, that does make it more challenging for Nigeria to invest in healthcare. The government has fewer resources and given all the demands on the public sector, it is difficult for it to find the money to invest in vital infrastructure. With less revenue coming in due to commodity price decreases, it is hard to finance health system improvements and build the infrastructure necessary for quality care. However, as oil prices move up, the country will be in a stronger position to invest in healthcare.

JA: I think it will be important to monitor your subsequent reports to know which of the countries you surveyed are making progress and which ones are falling behind. Until the next report, what is your outlook for healthcare governance for the countries you surveyed, especially those in sub Saharan Africa?

DMW: Like the countries we surveyed, the healthcare governance for countries in sub Saharan Africa is currently mixed. But with sound policy and regulatory decisions, we are confident that all of the countries in our survey can improve health governance and healthcare itself.

The new report is available here.

Recent Interviews

Latest Blogs

- The Museum of West African Art saga

- The complexity and complication of Nigeria’s insecurity

- Between bold is wise and wise is bold

- Prospects of port community system in Nigeria’s maritime sector

- Constitutionalism must anchor discipline in Nigerian Armed Forces

Latest News

- Africa needs €240 billion in factoring volumes for SME-led transformation

- ChatGPT is now the most-downloaded app – report

- Global trade to hit record $35 trillion despite slowing momentum

- CBN licences 82 bureaux de change under revised guidelines

- Green economy to surpass $7 trillion in annual value by 2030 – WEF