Deconstructing the $1 million venture capital fund for Nigeria’s creative industry

Feature Highlight

We expect the Ministry will, at least, triple the size of the fund before launch and that the Ministry, in strategic partnership with private investors, will aim to create multiple funds to target the different pain points in the country’s creative industry.

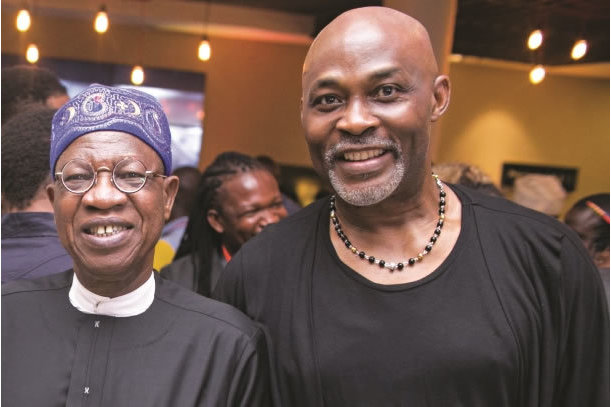

One must commend the Federal Ministry of Information, Culture and Tourism and its partners for successfully organising the maiden edition of the Creative Nigeria Summit last month. The summit, which held on July 17-18, was a bold step in thought leadership and engagement on some of the key issues affecting Nigeria’s creative industry. Some of the more exciting outcomes of the summit were the hints on policy direction for the industry provided by the Minister of Information, Culture and Tourism, Lai Mohammed, and the Acting President, Yemi Osinbajo.

Without a doubt, Osinbajo’s hint that tax breaks will be considered for players in the creative industry is a welcome suggestion. Tax incentives in Nigeria have historically been directed towards manufacturing, agriculture and extractive industries. Equally exciting is the idea of a $1 million venture capital fund, which Lai Mohammed proposed.

As conceived, the objective of the venture capital fund is to provide seed money for young and talented Nigerians to set up businesses in the creative industry. The announcement of a targeted venture capital fund for the creative industry is remarkable for many reasons. Macro-economic conditions seem right for investment in Nigeria’s creative sectors. Therefore, a venture capital policy will be an important addition to the traditional debt financing structure available in the industry.

Nigeria’s creative industry requires much more than a clinical financing approach. The combination of patient and intelligent capital à la exposure and industry-specific knowledge, which venture capital financing promises, are what the industry needs right now. It is useful to note that the announcement of the fund is in line with the objectives of the Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP) of the Federal Government. The ERGP aims to increase film production by 15% on an annual basis and generate $1 billion in foreign exchange by 2020 through exports of Nigerian films.

The establishment of a dedicated venture capital fund is the first of a number of strategic moves the Ministry wants to take to support the long-term growth of the creative sectors. However, the broad objective is to create an active market that allows both local and foreign investors to invest and exit with decent returns. Accordingly, the success of a venture capital policy in the creative industry will be a function of many factors and the Ministry will need to adopt some of the best practices which have been tested and proven in the private funds management industry, albeit with modifications necessary for public interest considerations.

The announcement of a venture capital fund for the creative industry raises some fundamental questions; and answers to these questions should go into developing the framework and structure for the proposed venture capital fund. Lai Mohammed reportedly said that, “20 people, each investing $50,000, are expected to help make up the required amount of 1 million dollars…so far, five people have volunteered to invest $50,000 each and expressed optimism that more investors will come forward.” (bold italics mine)

The words ‘volunteer’ and ‘help’ raise some concerns as to how the Ministry is thinking about the proposed venture capital fund. Such terminologies are more associated with charitable causes -- or at best, grant schemes -- than a serious venture capital financing strategy. But even if we assume that was a faux pas by the Minister, what is clear from the above quote is that the Ministry is looking to reach out to wealthy individuals to commit to the fund as limited partners. It appears the Ministry is not committing any of its own capital to the fund.

The foregoing observations raise questions of whether these individuals who have “volunteered’ to invest are ‘accredited investors’ within the context of securities regulation. It is also not clear what entity is carrying out the marketing of the fund. Meanwhile, it appears marketing activities are in full swing. There are questions around compliance with securities laws regarding venture capital fund formation that have to be addressed. If the fund is not captive as it appears, the marketing, formation and investment of the fund monies will come within the purview of securities regulation. Getting the fund structure right from the outset is critical for the fund to achieve its desired objectives. This is critical to attracting the right quality of talent and capital, and also from a risk management perspective.

It is useful to note that Ministries, Departments and Agencies (MDAs) of government are not immune from tortious claims and can be liable to damages under the doctrine of regulatory negligence. Accordingly, an unaccredited investor will be able to, in the right circumstances, make a claim for monetary damages against the Ministry and its partners.

Another critical point of reflection is the question of who the managers of the proposed creative industry fund are, or should be. Whilst the Ministry may decide to call for applications from the existing pool of generalist fund managers that are available locally, there are no known fund managers focused on the Nigerian creative industry. We think that government should also consider broadening the search for a management team locally and internationally, while aiming to receive the best combination of sectoral expertise and reliable fund management credentials.

The Ministry may also decide to handpick and corporatize an assortment of professionals and finance operations for the first fund cycle after which the team could morph and independently raise subsequent funds on a management fee basis. Regardless, resident, as opposed to consulting, sectoral expertise should be a crucial factor for qualifying fund management teams given the inherently risky nature of financing, especially, film projects. Typically, in a movie project, all investor’s monies are completely used up before returns start to materialize. This is an additional reason accreditation of angel investors may be important. Also, although film funds are structured like typical venture funds, there are significant differences in terms of the legal structures for channelling investment funds.

In any event, the Ministry will have to put some girth in the game by committing its own capital to the fund in order to inspire investor confidence and to demonstrate alignment with the broader objectives of the fund. Such commitments may be subject to a programmed withdrawal and sale of its participating interests.

The success of the proposed venture capital fund also has to be situated within the context of intellectual property (IP) law. An efficient intellectual property administration is required to attract (and sustain) both talent and capital to the creative industry. There is a need to further strengthen Nigeria’s intellectual property law from an administrative point of view. There should be an introduction of legal principles that make it easier to administer and protect intellectual property rights.

For instance, contrary to what obtains in jurisdictions like the United States, there exists no standalone right by which an artist can protect his or her personality or image under Nigerian intellectual property law. Hence, image/personality rights continue to be one of the most abused creative industry rights in Nigeria. As of date, an artist that intends to protect personality rights will have to rely on common law protections of passing off or constitutional guarantees of right of privacy, which by many standards, is a far more complex approach to enforcing or protecting intellectual property rights. These underlying IP rights, are critical to an investor from a financing standpoint because the monetisation of these rights could help mitigate potential investment losses.

But then, it’s not just a government play all through. Film/music/content distribution and producing companies will need to evolve by standardizing operations and restructuring their teams in order to reposition their companies to attract investors, either within the context of fund management or direct investments.

We have a few other expectations. We expect that the Nigerian government will follow through with this proposed fund. A similar policy announced for the technology industry a while ago has been dogged by allegations of government’s failure to fulfil its capital commitments, thereby, stifling the operations of the fund. This is a very bad precedent for the industry. Government participation should be the reason accredited and or sophisticated investors partake in a fund; not otherwise.

Furthermore, we expect that the Ministry will issue clear policy guidelines on venture capital finance for the creative industry. We also expect that the proposed tax incentives targeted at the Nigerian creative industry will have been implemented before the official launch of the proposed fund. We expect the Ministry will, at least, triple the size of the fund before launch and that the Ministry, in strategic partnership with private investors, will aim to create multiple funds to target the different pain points in the country’s creative industry.

Olubunmi Abayomi-Olukunle leads the private equity and venture capital transactions team at Balogun Harold.

Other Features

-

Building health systems for Africa’s vaccine sovereignty

The imperatives of reducing risk, strengthening markets, securing health futures

-

Analysis of CBN’s new regulations on cash management and dual ...

By revising cash policies and mandating dual connectivity for payment terminals, the Central Bank of Nigeria seeks to ...

-

Africa’s crypto investment market: where growth may emerge next

Africa’s crypto investment market: where the next growth coould explode.

-

Lessons from the 2025 Goalkeepers Report: What kind of innovation ...

The 2025 report issues a clear call to action for policymakers and engaged citizens.

-

Profit: The most powerful engine for scaling impact, dignity, and ...

The most prosperous countries in the world are not those with the most aid programmes. They are those with the most ...

-

Expect turbulent asset markets in 2026

The negative impact of Trump’s tariff and immigration policies will be felt more acutely in 2026.

-

The scars of partition

Contrary to his rosy assurances, partitions often result in tragedy, as borders drawn by cartographers rarely align ...

-

Best site to sell Bitcoin in Nigeria (Fast BTC to Naira in 2026)

Apexpay stands out because it focuses on what Nigerian users actually want: speed, good rates, and simplicity.

-

The quiet influence of securitisation in financing Africa's energy ...

The scale of Africa’s energy transition demands financial solutions that are modern, secure, and scalable.

Most Popular News

- Artificial intelligence can help to reduce youth unemployment in Africa – ...

- NDIC pledges support towards financial system stability

- Global job quality stagnates despite resilient growth – ILO

- MTN is named the best mobile Internet leader in Nigeria

- Afreximbank ends its credit rating relationship with Fitch

- FRC Chairman commends NDIC for prompt remittance of operating surplus