Cheta Nwanze, Lead Partner, SBM Intelligence

Follow Cheta Nwanze

![]() @Chxta

@Chxta

Subjects of Interest

- Fiscal Policy

- Geopolitical Analysis

- Governance

- Politics

Nigeria continues to search for pathways to universal basic education 12 Oct 2022

Formal, Western-style primary education in Nigeria began with the founding of the then-colonial territory's first primary school in Badagry in 1843 by Christian missionaries. Soon after that, more primary schools were started in other parts of what is now the South-West geopolitical zone of the independent Nigeria. Educational systems provided by Islamic missionaries in Northern Nigeria stifled the establishment of ‘Christian’ schools in those areas but eventually, in 1898, schools were set up in Bida and Zaria by the Church Missionary Society (CMS).

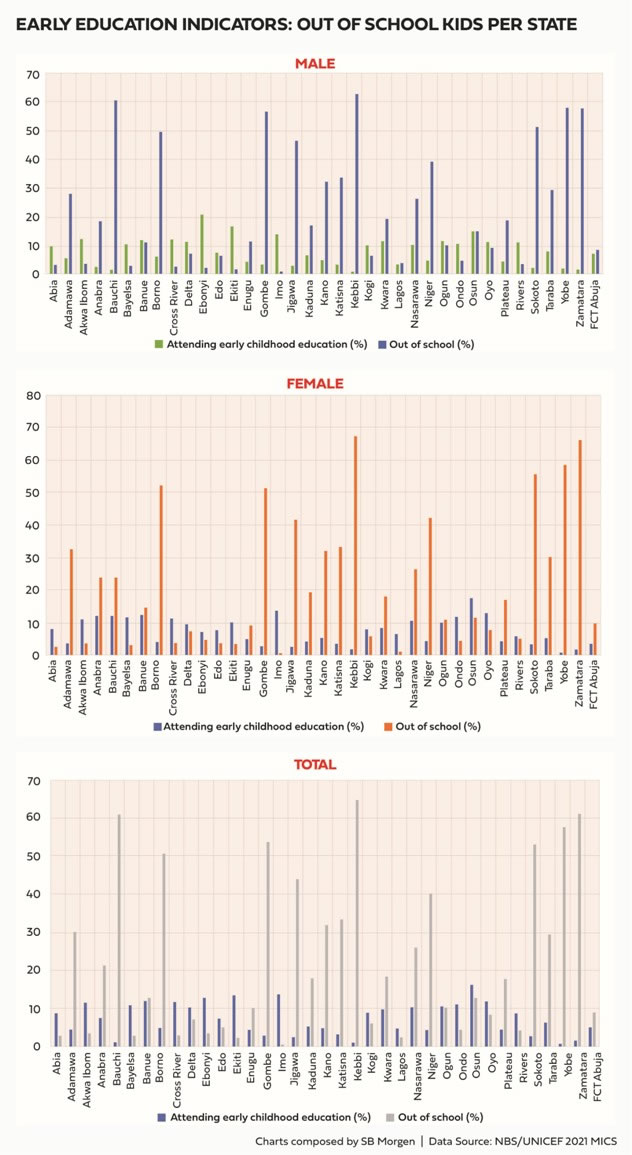

The cultural resistance to the provision of formal, primary school education has persisted and continues to affect access to basic education in Nigeria over a hundred years later. According to UNICEF, children who are out of school – as a percentage of the total school-age-children population – ranged from 48-60 percent, while enrolment for early education rates were 3-7 percent, in 2021.

The case of the Northern girl-child is more troubling. Statistics by UNICEF shows that roughly 60 percent of female children in the North are out of school. The figures for out-of-school children (OoSC) for female children in the core Northern regions are around 60 percent. The numbers in other parts of the country are somewhat better but still worrisome. All the regions of the country have a combined approximately 20 million OoSC, which is 8 percent of the world’s total, which is disproportionately high given that Nigeria has only 3 percent of the world’s population.

These Nigerian children are being deprived of the opportunity to learn a suitable foundation in basic subjects like mathematics, science, and social studies, which puts the eventual cost of their literal inadequacy and undeveloped productive capacity to the Nigerian economy at a whopping $40 billion, or roughly 7.83 percent of the country’s $432 billion GDP.

Efforts by the government at addressing the problem of school-age children not enrolled in schools include its ‘free’ and compulsory education policy. The Universal Basic Education (UBE) programme was launched by President Olusegun Obasanjo in 1999 to provide free, compulsory, and universal primary, secondary, and adult education to Nigerians in order to achieve 100 percent literacy levels in due time.

As part of the strategies for achieving the overarching target of UBE, the government seeks to inculcate the value of education in the citizens; ensure high school completion rates; provide suitable alternative learning opportunities in the system for young persons who have had their schooling interrupted; and help Nigerians to acquire the right levels of literacy, numeracy, ethical, communication, and civic competence needed for successful learning and productivity for the rest of their lives.

The Compulsory, Free Universal Basic Education Act, 2004 gave legal backing to the programme in alignment with the Global Education for All (EFA) initiative, the then-Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and National Development Goals as laid out in the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS) document.

One of the key hindrances to adequate provision of primary school education is the lack of qualified personnel. The Universal Basic Education Commission

(UBEC) said a personnel audit it conducted shows that the country has a shortage of 277,537 teachers for basic educational purposes. Retiring teachers are not being adequately replaced, and between 2015 and 2019, 28 of Nigeria's 36 state governments did not employ any new teachers at all. Newspaper reports in 2019 said Rimawa Primary School in Goronyo, Sokoto State, had 10 teachers attending to 1,170 pupils – a common pattern in the area.

The teacher shortage was not limited to the simple lack of personnel. ‘Hidden shortage’, which refers to available teachers not having the grounding for the subjects they teach students, was also prevalent. There was also ‘suppressed shortage’, a situation where some subjects are deliberately not made adequately available for teaching because of a lack of qualified personnel for their teaching. Such subjects are either excluded in the timetable or classes are merged because of limited teacher numbers. And there was also ’modernised shortage’, which is the outcome of trained teachers that are ineffective and redundant because they have not stayed in touch with new knowledge in their disciplines. Inadequate and infrequent salaries for teachers and lack of infrastructure for primary school education were other challenges.

The policy frameworks for addressing these issues are technically in the domains of the state and local government tiers. But the success of Nigeria's Universal Basic Education policy is very dependent on the capacity of the local governments as laid out by Decree No 3 of 1991. The military fiat made the provision and maintenance of primary education one of the functions of the 774 Local Government Areas (LGAs). Giving the LGAs the responsibility for the provision of primary school education was sensible in principle: They are closer to the people and so would be able to know the peculiarities of the areas they are to serve. In reality, however, it has been akin to getting an elephant to walk on stilts.

The local governments are not adequately empowered for the roles they have been given, and this has greatly affected the success of the attempts to provide primary school education to all. The UBE itself is well structured, but the quality of governance required to fulfil its set objectives is not available. The local government structure that is meant to implement the policies, in conjunction with the state government structure, has found itself being sabotaged by a partner that is intent on controlling the resources constitutionally allocated to it without fulfilling the assigned responsibilities.

The Obasanjo administration tried to solve the problem by setting up a technical committee that was tasked with identifying ways to achieve the restructuring of the local government system. Following the report of the committee, the federal government's accepted recommendations including recognition of the constitutional autonomy of local government as the third tier of government, abolition of the State-Local Government Joint Account, and direct remittance to each local government council of its share of the Federation Account.

The acceptance of these recommendations has not brought the needed changes because their implementation is dependent on constitutional amendments that have not been made. This is partly due to the resistance of the state governors who are unwilling to lose their power over the LGAs.

Pending when the devolution of power would be achieved, the federal government recently launched the Accelerated Basic Education Programme (ABEP) to deal with the problem of OoSC. The ABEP is an abridged system aimed at school-age children who have had their education disrupted or have never been enrolled in school at all. The programme is under the control of the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC), with partnership support from the European Union and Plan International Nigeria – an organisation promoting children's rights and equality for girls.

The Federal Ministry of Education has expressed its commitment to using policy frameworks and monitoring systems to ensure the success of the ABEP, after the success of the pilot phases in Yobe and Borno states. At the launch the programme, the Executive Secretary of the NERDC, Professor Ismail Junaidu, said the council had teacher training guidelines engineered to help states and partners achieve the goals of ABEP. "The Accelerated Education Programme is today used as a standard descriptive term for the flexible, age-appropriate education programme and runs in an accelerated timeframe that provides pathways to mainstreaming learners into relevant levels of schooling based on proper profiling,” he said.

The overarching objective of ABEP is to provide an alternative educational programme that is suitable for the needs of overage out-of-school children and youths, and in the process mainstream them to regular school programme or provide them with alternative career path through enrolment into a vocational training centre.

The Chairman of the House Committee on Basic Education, Professor Julius Ihonvbere, said the National Assembly had completed the constitutional amendment process of moving Basic Education from Chapter Two of the Constitution to Chapter Four, which would make it a right for the Nigerian citizen. He added that it is the responsibility of government to provide the schools, teachers, teaching aids, and productive and functional curriculum.

I hope that this and other programmes would be used to provide the quality of governance needed to return the nearly 20 million children who are currently out of school back to the classrooms where they belong. Failing to get them in school portends disaster for all of us.

Cheta Nwanze is Lead Partner at SBM Intelligence.