Jide Akintunde, Managing Editor/CEO, Financial Nigeria International Limited

Follow Jide Akintunde

![]() @JSAkintunde

@JSAkintunde

Subjects of Interest

- Financial Market

- Fiscal Policy

What to make of OPEC's oil supply-cut agreement 05 Dec 2016

A strong price rally greeted the deal reached on November 30 by members of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to cut oil supply by 1.2 million barrels a day, effective January 2017. Within 24 hours of the agreement, oil prices surged by 8 percent to $51 a barrel – the first time in the year. Whether or not this deal will unravel as some analysts anticipate, it will remain the catalyst for oil prices in the next one to two months. Thus, the deal represents a happy ending to a terrible year in which oil prices averaged the lowest level in five years.

Cold Agreement

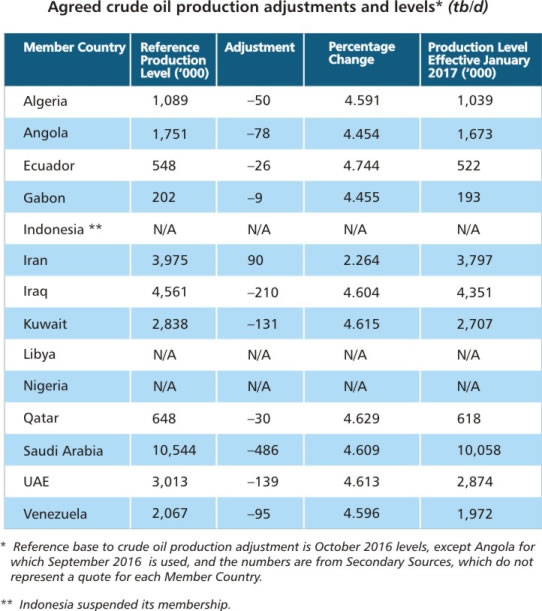

It was in the interest of all members of OPEC for oil prices to rise above the $45 a barrel average of the last few months. But with some members cushioned by large reserves savings, the effect of the low prices of 2016 has been unevenly felt. Nevertheless, the agreement represents cold calculations writ large. Most notable is that Saudi Arabia, which produces 10.5 million barrels per day – accounting for 30 percent of OPEC's reference production – did not contribute the highest percentage cut. Ecuador, which produces 548,000 barrels per day (bpd); Kuwait, which produces 2.8 million bpd; and United Arab Emirate, which produces 3 million bpd, made the highest marginal percentage contributions to the cuts, in that order of magnitude.

Also significant is that Venezuela, which has been in a lengthy fiscal crisis, and Gabon, which produces only 202,000 bpd had to make the average 4.5 percent cut by most of the members. This makes OPEC probably the association that is least considerate of its less fortunate members, compared with any other group in the world. Given the commitment of Saudi Arabia to the pursuit of its interest without due consideration to other members, OPEC will never be able to match its influence in the energy market with respectability. The withdrawal of Indonesia from the cartel on the grounds that it was unable to make contribution to the supply cut agreement may as well signal the new round of weakening of OPEC's membership.

Nigeria's Abracadabra

There is no clear one narrative about Nigeria with regard to the agreement. On the one hand, Nigeria's Minister of State for Petroleum Resources, Dr. Ibe Kachikwu, pulled off an enviable diplomatic feat for the role he played in facilitating the agreement. He was very active within OPEC and in the international media canvassing for the need to cut supply in order to have oil price rally. It was a difficult job that entailed highlighting the fiscal challenges brought on oil producers by low prices, with Nigeria being one of the extreme cases of lack of resilience to oil revenue shocks.

But Kachikwu himself was resilient and unrelenting. For that, Nigeria had its cake and ate it. The country was exempted from the supply cut. Libya – which has been struggling to get its oil industry back on track after the civil war – is the only other country exempted from OPEC's supply cut. Even minor producers like Gabon and Ecuador, and Venezuela at the brink of economic collapse, were not spared the cuts.

On the other hand, Nigeria's exemption from the supply cut brings into question the official data that says oil production in the country has ramped up to two million barrels per day. In June, Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) announced that the country's oil production had risen to 1.9 million bpd. On the heels of the putative production recovery, Dr. Kachikwu led a road show to China that reportedly garnered $80 billion in various oil and gas investment commitments. Even as production made further statistical recovery to 2 million bpd, the oil minister also announced a $15 billion oil prepayment deal with India.

However, these deals and buoyant production data have failed to ease the fiscal pressure on government's programmes, including the 2016 capital budget which has been implemented to no more than 50 percent. Moreover, Fitch recently stated its doubts over possible realisation of the oil prepayment deals. This was extrapolated from the inability or unwillingness of the President Muhammadu Buhari administration to strike a deal with the Niger Delta militants, who have continued to sabotage oil installations. As if to confirm this, and in contradiction of the negotiations government was having with leaders of the Niger Delta to restore stability in the oil economy, the military recently launched what it code-named “Operation Python Dance” to confront the militants.

Arguably, Dr. Kachikwu would not have been able to persuade other OPEC oil ministers to grant Nigeria the exemption from the supply cut based on the official data he had endorsed locally. Most probably therefore, the actual reality of Nigeria's fiscal pressure, which has been raising international concern about stability of the country, may have informed OPEC's considerations and not the oil industry data supplied to the local market.

Oil Geopolitics

The OPEC deal suggests nothing about rapprochements between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The mutual antagonism between the two countries has fuelled geopolitical tensions, even as the two countries are pitted on the opposite sides of the proxy wars in the beleaguered Middle East. The Saudi-Iranian imbroglio had delayed the supply-cut agreement OPEC eventually reached on November 30th.

Saudi Arabia agreed a marginal cut to its production. But the deal betrays insistence by the country on retaining its market share. This explains the across-the-broad production cut (excepting only Nigeria and Libya). Iran seemingly was awarded 90,000 additional barrels. However, some analysts have pointed this out as a computation error. In actual fact, Iran's production allocation will fall to 3.797 million bpd when the OPEC agreement kicks in in January 2017, compared to its 3.975 million bpd reference production.

But most certainly, the price rally which OPEC's supply cut generated is expected to spark a revival of shale oil production in the United States. In broader equity rally following the agreement, shares of shale oil producers Whiting Petroleum Corp and Continental Resources Inc. rose 32 percent and 25 percent, respectively.

The early sign of possible unravelling of the OPEC agreement would be Saudi's body language in response to a shale revival. It had been a deliberate strategy of Saudi Arabia to squeeze US shale producers out of the market by its strategy that depressed prices while maintaining market share. But more generally, production increases in the US will reassert the supply glut, dragging down prices and extending the fiscal misery of producers including Nigeria.

Centrality of Non OPEC Producers

The OPEC agreement will become effective, depending on whether non-OPEC producers – mainly Russia – contribute 600,000 barrels a day in addition to OPEC's supply cut. In the immediate term, Russia has signalled to cut 300,000 bpd. The contingency of production cuts by non-OPEC producers is a significant risk to maintaining the OPEC agreement. Russia will be constrained by its economic recession and depleting reserve savings. Further constraint would be the need to fund President Vladimir Putin's gunboat diplomacy in Europe and Syria. However, what Russia would lose from oil it can compensate for by pumping more gas into the market. Whether that would also be tantamount to a deal-breaker is anyone's guess.

In the final analysis, this OPEC's deal rests too heavily on contingencies. OPEC has no enforcement mechanisms. In the past, its members secretly flouted their supply quotas. This term, more extraneous factors to oil production, including advances in renewable energy, will limit the extent to which supply cuts can drive up oil prices. Thus, the math most members of OPEC will be preoccupied with is the moving average income derived from higher oil prices with the lower supply quotas, compared with what obtained in 2016 prior to the November 30 agreement. Whatever the figure, it would be pointless to compare it with the three-year average ending in mid-2014.