Jide Akintunde, Managing Editor/CEO, Financial Nigeria International Limited

Follow Jide Akintunde

![]() @JSAkintunde

@JSAkintunde

Subjects of Interest

- Financial Market

- Fiscal Policy

Nigeria needs adjustment in monetary policy to benefit from AfCFTA 20 Mar 2020

Central Bank of Nigeria’s headquarters, Abuja

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which will become operational on July 1, 2020, could increase intra-Africa trade by 36 percentage points – from the current 17 per cent to 53 per cent – in two decades. According to Vera Songwe, Executive Secretary, United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the free trade agreement could increase trade between African countries by $70 billion by 2040. But if this gain is simply structural, by redirecting Africa’s trade with the rest of the world to the continent, AfCFTA would have very little economic benefit for the continent.

On the contrary, AfCFTA is expected to serve as a catalyst for increasing economic output of African countries. But for this to happen, a number of policies that have curtailed output growth have to be addressed in the 54 countries that are parties to the free trade agreement. In Nigeria, the constraints to economic growth and industrial production range from structural issues in the economy to poor infrastructure, preference for foreign products, high cost of inputs, and lack of access to finance.

These issues have not eluded the policymakers. For instance, successive Nigerian governments since 1999 have identified the need to diversify the economy from high dependency on revenue from oil export. Also, between 2015 and 2020, the nominal value of aggregate budgetary allocation for capital expenditure increased by 241 per cent, from N722.20 billion to N2.46 trillion. Moreover, governments at the federal and state levels, the banks and some international organisations have been working to increase financial access – including access to credit – in Nigeria.

But progress on these issues has been weak at best. The dependency on oil revenue has not shifted; revenue from crude oil export still accounts for over 90 per cent of government’s foreign exchange earnings. The good news, though, is in the area of infrastructure development where the delivery of ongoing projects will, to some extent, improve haulage and ease the stress of interstate commuting due to bad roads.

Removing the clogs to Nigeria’s productivity increase is very key for the country to benefit from AfCFTA. Nigeria accounts for 20 per cent of Africa’s GDP and the country is rich in factors endowment. As such, Nigeria should at least proportionately share in the projected increase in intra-Africa trade. For this to happen, the country needs to remove the policy barriers to its potential productivity surge. Two of the necessary policy reforms – interest rate and the foreign exchange regimes – are monetary, and are the focus of this article.

Uncompetitive Interest Rate

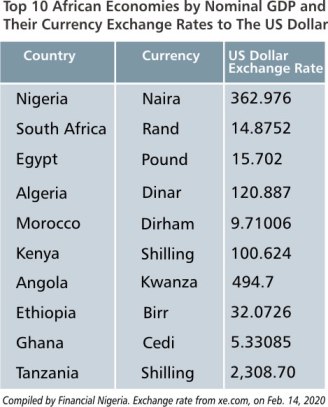

The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) at its January 2020 Monetary Policy Committee meeting retained its Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) at 13.5 per cent. The MPR, which is the rate at which the CBN lends to banks, is, of itself, very high. It is also the highest among the 10 largest economies of Africa, except Ghana and Angola.

Given that inflation is also in double digits in Nigeria, banks charge as high as 30 per cent on final credit to businesses, to allow for a decent spread and accommodate the risk of defaults. This high interest rate is prohibitive for established or new businesses and for big businesses or SMEs. While reducing interest rates alone will not bring down the cost of doing business, high interest rate is undoubtedly a big challenge for increasing productivity in Nigeria.

Not oblivious of this, the CBN attempts to use its less influential tool, development finance, to address the problem of high cost of credit. The reserve bank has floated several funds, which are being managed mainly by the national development banks (NDBs), including Nigerian Export-Import Bank, Bank of Industry, and Bank of Agriculture. These institutions provide interest rates that are below market rates, officially in the topmost range of single digit.

Whereas the NDBs have started addressing the problem of distribution associated with their centralisation by disbursing credit through the commercial banks, access to the funds remains constrained and discriminatory. The funds, which have increased CBN’s commitment in the credit market, nevertheless represent a small proportion of loanable funds in the market. As at year end 2018, the net loans and advances to the NDBs in the country was N918.47 billion, representing just 3.3 per cent of the aggregate credit to the domestic economy (net), which stood at N27.57 trillion, according to data from the draft CBN Annual Report 2018. If the high interest rates at which the commercial banks lend were fire that has engulfed a building, CBN’s low-cost development financing would amount to using spittle to try to quench the fire.

Foreign Exchange Restriction

Nigerian businesses in general, but SMEs in particular, face daunting challenges in their quest for foreign exchange to carry out their operations. The challenge of access to foreign exchange is at different levels in the country. First, foreign exchange rates diverge across the official and parallel markets. Currently, the variation is above 15 per cent. This disadvantages access via the parallel market, the more perfect market for foreign exchange in Nigeria, where smaller firms stand better chances of sourcing foreign exchange.

Second, the opportunity for arbitraging promotes corruption in the foreign exchange market, undermining the policy objective for divergence of rates. This has been a long-term problem. To the extent that the foreign exchange rates don’t achieve convergence – i.e. variation of not more than 5 per cent – the policy targets of rate variation, in this case stimulating domestic production in specific sector by boosting foreign exchange liquidity in those sectors, will be elusive.

Third, CBN’s current policy also entails multiple rates in the official windows for foreign exchange. Different rates apply to different transactions and sectors. Because of supply shortfall relative to demand, sectoral players don’t have equal access to the official FX subsidy. The subsidy also undermines cross-sectoral competition, as not all sectors are covered.

Overhauling Monetary Policy

It is one of the many contradictions of the Nigerian economy that, although it is the largest in Africa, Nigeria has one of the highest interest rates in the continent. Similarly, the Nigerian currency is also one of the weakest among African currencies against the US dollar, although the country is the top oil exporter in Africa. But whereas there is consensus both in industry and policy circles for a much lower interest rate, the desirability of a stronger naira has often been contested.

The inflationary pressure to be stirred by significant reduction in the MPR has been a major consideration of the CBN. But while the concern subsists, the central bank is nevertheless ameliorative of the high cost of credit. Without prejudice to the relative price stability that this cautionary – but still contradictory – approach has achieved, it is evident that it provides an interminable path to significant progress in economic production in the country.

Thus, the CBN has to consider other options. One is closer home. Whereas its portfolio of development finance has increased in nominal terms over the last decade, the CBN could grow it considerably more, but across the value chains of sectors. This approach should de-emphasise the firm size as it is currently the case with targeting SMEs. Instead, firms of various sizes should be provided affordable credit to develop key value chains. This will enable the linkages that are necessary to increase production, distribution, processing and export in sectors.

With regard to the foreign exchange policy, the main advice against the continuation of the current market stratification is its deterrence to foreign direct investment into the country and capital repatriation by Nigerian exporters. Nigeria now lags smaller economies in Sub Saharan Africa in attracting FDI. Whereas AfCFTA is expected to catalyse higher FDI to Africa, the risk posed by extant foreign exchange policy in Nigeria will remain a stumbling block for attracting the investments.

The clear option is for CBN to pursue rate convergence more determinedly. It has to close the arbitrage opportunity of its multiple exchange rates. This doesn’t even constitute a pivot away from the current managed float of the naira value. Convergence of rates will even the playing field for local producers who require foreign exchange for inputs; it will also attract foreign investment and encourage capital repatriation by exporters into the country.

President Muhammadu Buhari had hesitated before he eventually signed the AfCFTA agreement. The broadly-shared concern was that Nigeria may become an export market to be exploited by other African countries. But the goal of AfCFTA is that it should be a win-win for all the countries participating, helping them to increase economic output and create jobs.

However, the concern about trade dumping in Nigeria might as well be a self-fulfilling prophecy if the challenge of factor competitiveness is not addressed by Nigerian policymakers. For Nigeria to be competitive with other African countries that currently have more favourable policies and macroeconomic stability, broad policy changes and improved policy outcomes are required.