Cheta Nwanze, Lead Partner, SBM Intelligence

Follow Cheta Nwanze

![]() @Chxta

@Chxta

Subjects of Interest

- Fiscal Policy

- Geopolitical Analysis

- Governance

- Politics

How Nigeria can start retaining talented citizens 14 Jun 2019

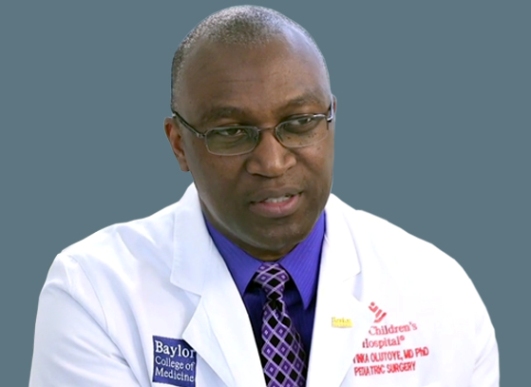

Nigeria-born Oluyinka Olutoye, Co-Director, Texas Children's Fetal Center, United States

Human capital flight is not new in Nigeria. Although the country didn’t exist until 1914, massive human capital flight from the country’s territory dates back to slave trade, particularly from the 16th century. A Nigerian popular television commercial in the 1980s, which implored “Andrew” not to “check out”, suggested the country had begun to recognise the problem of human capital flight or brain drain.

If we recognised the problem, in the final analysis, we didn’t commit to solving it. As a result, there is even a current emigration surge that sees Nigerians moving en masse to Canada, Australia, the United States, Britain, South Africa, Ghana, and other countries. Among those who are leaving the country to look for opportunities abroad are professionals, such as doctors, accountants and tech gurus. There are also post-graduate students who have had enough of the poor quality of education offered by Nigerian institutions.

The medical field is one of the areas that are hardest hit by brain drain in Nigeria. 5,405 Nigerian-trained doctors and nurses are currently working in UK’s National Health Service. The figure, which was recently released by the British Government, showed that Nigerian medical personnel constitute 3.9 percent of the 137,000 foreign staff of 202 nationalities working alongside British doctors and nurses in the United Kingdom.

The statistics definitely shows that Nigeria is not the only country contributing human capital to developing and maintaining the UK healthcare system. But it also highlights that the Nigerian contribution is outsized. Nigeria is 2.6 percent of world population; and Nigerians, or people of Nigerian descent, constitute 0.29 percent of the population of the UK.

Even more Nigerian doctors will be able to join their colleagues already practicing in the UK. Thanks to Brexit, medics from the European Union have been leaving Britain. The British government plans to fill the void by allowing more doctors to come in from the Commonwealth countries.

In the meantime, the physician-to-patient ratio in Nigeria has dipped further, from 1:4,000 to 1:5,000. This is far below the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s recommended 1:600. But the ratio is 1:300 in UK, where the government is keen to maintain high professional standard of care.

Nigeria is not only losing, by the numbers, its professionals and unskilled labour to foreign countries. Of the almost 200 medical doctors set mates that graduated in 2006 from the University of Benin, less than 10 of them are still in the country. While I am aware of this because of a close connection, two notable talents Nigeria has lost are worthy of specific mention. Indeed, they are very familiar to Nigerians because of their recent feats, and because we like to celebrate our best people regardless of where they are.

Nigeria-born Oluyinka Olutoye in 2016 achieved a rare feat in medical practice. He and his team in the U.S. state of Texas successfully operated on an unborn baby at 16 weeks. Scans had shown the unborn child had a tumour. Dr. Olutoye led his colleagues to extract the foetus; removed the tumour; and returned the foetus to the mother’s womb. The pregnancy was carried to term and the baby was delivered in good health.

The other rave example is Ufot Ekong. In his first semester at Tokai University, Japan, he solved a mathematical puzzle that student had been unable to solve for three decades. Ekong, who is now 29 years old, went on to break a 50-year academic record when he graduated as the “Best All Rounder”. He graduated with first-class in electrical engineering.

Remarkably, Ekong worked two jobs to pay his tuition through school, and ran a retail clothing and accessories shop. His talents extend to linguistics; he is fluent in Japanese, French, and Yoruba, and had won a Japanese language award for foreigners. Currently working for Nissan, he is studying for his master’s degree programme in Electric/Electronic Systems Engineering; and he has already registered two patents for electric car design.

Either in terms of the number of Nigerian professionals emigrating, or the fact that some of them are among the country’s best talents, there is cause for concern about the prospect of economic development in Nigeria. Because of the digital age, we know there are very talented Nigerians, even though they are shining in other countries. The benefit of knowing these geniuses may not entirely be insignificant for social development in Nigeria; but the economic impact of not having them here is immense. It, therefore, beggars belief – if not a cruel irony – that Chris Ngige, a doctor and the erstwhile Minister of Labour and Productivity in the first term of the President Muhammadu Buhari administration, would suggest that the country can afford to keep losing its doctors to other countries.

How does the country begin to address the problematic high human capital flight from the country? One of the ways is to dramatically raise the level of investment in education and health. This is where we would start to build a progressive society and an environment that is conducive to human capital to function maximally. The emigration surge in the 1980s was driven by the falling investment in the closely interlinked sectors. If fallen government revenue induced the lower investment, subsequent governments have normalised it.

The experience from the developed countries is that raising investment in human capital causes fertility rate to reduce. Nigeria is currently producing more than enough children that it can cater for. According to data from UNICEF, Nigeria accounted for a third of new-borns on January 2018. A great percentage of the children will probably join the already 13 million out-of-school children when they grow older as actual per capita spend on education and healthcare continues to drop in the country.

However, the question arises: Where will the funding for human capital investment come from in the constricted fiscal space? We have to look for short- to long-term solutions. In the short-term, government has to restructure public expenditure. By cutting wasteful spending and reducing the number of political appointees, governments at federal and state levels can free up more money for investment in education and healthcare.

This measure will help optimise the impact of the new fiscal strategy of the federal government that seeks to reduce its stakes in the joint ventures with the multinational oil companies. The revenue gain from the asset sale is one off, but its use should make long-lasting economic impacts.

In the medium- to long-term, government needs to deliver on the structural transformation of the economy. The value chains of multiple sectors, including oil and gas, agriculture, solid minerals and tourism have to be developed. This is the practical way to deliver on the much-talked-about diversification of the economy. In that scenario, the SMEs sector will begin to help raise national productivity, create employment, reduce poverty and generate more tax revenue. The space for Nigerian talents to express themselves in the local economy will increase. The increased opportunities that this will generate in the private sector will be a boon for Nigerian professionals, entrepreneurs and the entire workforce.