Decarbonizing shipping: What role for flag states?

Summary

UNCTAD supports the Getting to Zero Coalition and promotes efforts to achieve sustainability, helping developing countries adapt and build resilience in light of the climate emergency.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) member states agreed in 2018 “to reduce the total annual GHG emissions by at least 50% by 2050 compared to 2008” as part of the “initial IMO Strategy on reduction of GHG emissions from ships”.

In order to support achieving this objective, the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) and other maritime industry associations propose the establishment of a research and development [funding]. This fund is to be financed by a contribution of “two US dollars per tonne of marine fuel oil purchased for consumption”. The private sector-led Getting to Zero Coalition writes that “shipping’s decarbonization can be the engine that drives green development across the world.”

“The falling costs of net zero carbon energy technologies make the production of sustainable alternative fuels increasingly competitive. Determined collective action in shipping can increase confidence among suppliers of future fuels that the sector is moving in this direction.”

UNCTAD supports the Getting to Zero Coalition and promotes efforts to achieve sustainability, helping developing countries adapt and build resilience in light of the climate emergency.

According to a working paper by the International Monetary Fund, “the environmental case for a maritime carbon tax is increasingly recognized”. The Environmental Defence Fund argues that “meeting the IMO’s 2050 target represents $50 billion to $70 billion per year for 20 years spending, but this is also a revenue opportunity.”

The World Bank, also a supporter of the Getting to Zero Coalition, highlights that a large share of this investment opportunity could lie in developing countries.

A large part of these investments will have to be made ashore, including by energy providers and in seaports. As regards ships, their owners will have to invest in the renewal of the fleet, and new technologies.

What does this mean for the flag states where the ships are registered?

Flag states have an important role to play in enforcing IMO rules because they exercise regulatory control (i.e. apply the law and impose penalties in case of non-compliance) over the world fleet on diverse issues, ranging from ensuring safety of life at sea, protection of the marine environment, and the provision of decent working and living conditions for seafarers.

In the context of the implementation of the IMO GHG emissions strategy, flag states will have to ensure that ships are compliant with applicable IMO rules. In addition, they could also provide incentives for the ships registered under their flag to reduce CO2 emissions, and potentially play a role when it comes to ensuring the collection of future fees or contributions associated with CO2 emissions.

The above-mentioned ICS proposal, for example, suggests that contributions to the proposed fund will be made “commensurate with the ship’s annual fuel oil purchased for consumption, as verified by the flag State.”

Flag states could see such involvement also as a business opportunity, where more transparent and reliable flag states provide better services than others. In addition, many major flag states are themselves also affected by the impacts of climate change.

For example, the Panama Canal is confronted with a shortage of fresh water; Liberia has developed its National Adaptation Plan to mainstream climate change adaptation into planning and budgets; and the Marshall Islands are among the low-lying SIDS (Small Island Developing States ) most at risk from sea-level rise. It should thus be in these countries’ self-interest to support the reduction of global green-house gas emissions, including from shipping.

Status of CO2 emissions: a vessel registry’s perspective

Thanks to data generated from the automatic identification system (AIS) tracking system for ships, including information on each vessel’s characteristics, speed, type of fuel, and ballast situation, it is today possible to calculate estimates for CO2 emissions from each individual ship.

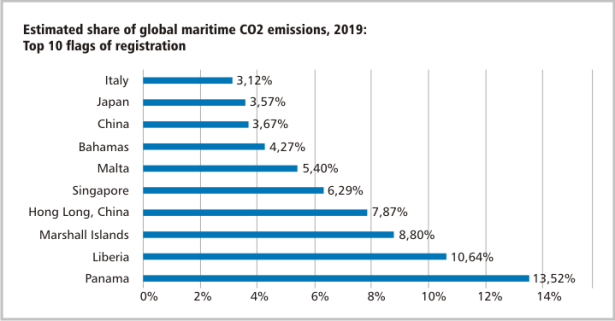

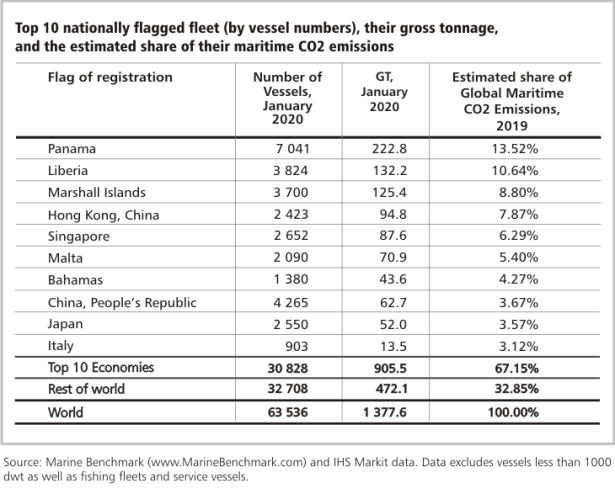

On this basis, ships registered in Panama, Liberia and the Marshall Islands, together, accounted for almost one third (32.96%) of CO2 emissions from shipping in 2019 (Figure 1). The same registries together represent 34.86% of the world total gross tonnage (Table 1).

Using the same metrics, in 2019, the ships (commercial vessels of 1,000 dwt and above) registered in the top ten economies accounted for 67.15% of the maritime CO2 emissions (table 1).

As of 1 January, 2020, these ten flags registered 48.52% of the world fleet (ships) and 65.73% of the world gross tonnage. World maritime CO2 emissions have risen by 8% between 2014 and 2019, based on the latest analysis from Marine Benchmark.

Their analysis also indicates that CO2 emissions have risen more steeply among the top 10 flag states – as much as 14%.

By sharing this data, we hope to encourage further discussions on options to achieve the objective of reducing CO2 emissions from shipping, and the interests and possible role that flag states could play in this endeavour.

Jan Hoffmann, Chief, Trade Logistics Branch, Division on Technology and Logistics, UNCTAD; and Alastair Stevenson and Torbjörn Rydbergh, MarineBenchmark. Source: UNCTAD

Related

-

IFC, Kobo360 invite innovators to pilot sustainable cooling in Nigeria

Sustainable cooling technologies represent a fast-growing business opportunity with particular importance to emerging ...

-

Worldwide transport activity to double, emissions to rise further - Report

The ITF Transport Outlook 2021 says that transport CO2 emissions can be cut by almost 70 per cent over the 2015-50 period ...

-

Tayo Bamiduro: How MAX is driving sustainable mobility across Africa

We need to transform the people part of our transport infrastructure in Africa.