Jide Akintunde, Managing Editor/CEO, Financial Nigeria International Limited

Follow Jide Akintunde

![]() @JSAkintunde

@JSAkintunde

Subjects of Interest

- Financial Market

- Fiscal Policy

Covid-19 to newly normalise inefficiency 13 Jul 2020

Picture showing President Muhammadu Buhari (right) not wearing a face mask while

meeting with other state officials

The world is stumbling onward to a new normal of physical distancing and working from home. Zoom has been the most popular herald of this new era, as religious, social and business meetings move en masse to the hitherto obscure platform that has had to quickly fix its egregious security holes.

Amid the Covid-19 lockdowns and partial reopening of businesses, Amazon’s market value soared by over 45 per cent, while the Dow Jones Index dipped more than 10 per cent as of June ending. Enterprises, including e-commerce, e-learning, e-payment, computer programming, and computer hardware manufacturing are projected to massively benefit from the seismic shift in the business landscape. Given the prospective broader use of technology, it appears we are heading to a very “cool” future.

But we urgently need to pause to think more deeply about this future. In its World Economic Outlook, June 2020 update, the IMF projected global GDP to contract by 4.9 per cent this year. This represents a downgrade, by 1.9 percentage points, of its previous dire forecast in April. Although many countries including Nigeria are projected to return to positive growth in 2021, their GDP would still be smaller than at the end of 2019. This is regardless of the lift in the fortunes of tech companies and a few others outside the sector.

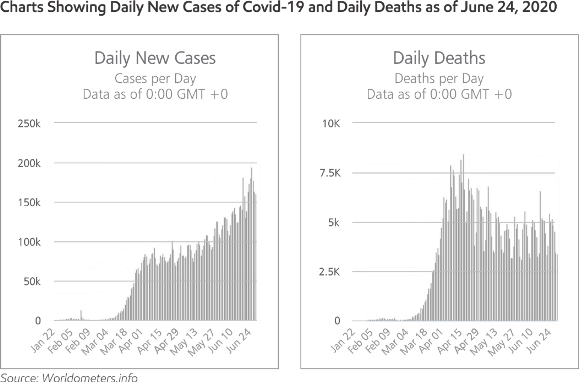

Very likely, a relapse to a more devastating phase of the pandemic is on the horizon, given upward trending of new infections around the world amid lethargy in fighting the pandemic. And as stimulus for payroll support in the countries that were able to enact them begins to taper off in the coming months, jobs data may become less assuring of sustained recovery in the labour market.

The fundamental question is whether the world can build on the foundation of Covid-19 responses that had hardened by the end of June. That foundation may be strong enough for holding only a house of cards.

The novel coronavirus has dazed our incompetent world since the virus was first discovered in China last December. First, policymakers and some highly regarded analysts take Covid-19 to be a black swan event. This is despite many years of warnings by some scientists, including Vincent C. C. Cheng, et all, about possible outbreaks of infectious diseases like Covid-19. The billionaire philanthropist, Bill Gates, had regularly echoed the warnings. Hollywood has severally dramatized the potential ravages of such outbreaks. But whereas policymakers were forewarned, they were not forearmed.

Second, the evidence is preponderant that China staggered in quickly informing the world about the new outbreak. Dr. Li Wenliang who blew the whistle on the disease in the Wuhan province where the outbreak originated was hushed and harassed by the state officials. Sadly, the 34-year old ophthalmologist who wanted to save the world from the deadly infection, later died from it.

Third, looking back now, many gaps are evident in the early responses to the outbreak. Global travel restrictions should have kicked in sooner. Physical distancing should have been observed in operating flights since January, if not from a week earlier. And whereas a few countries learned from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak in China in the early 2000s, which spread to 25 other countries, by including the wearing of face masks in the protocols for preventing Covid-19, it was much after the virus had gained ground in the U.S. and other (advanced) countries that public officials started asking people to wear face masks in public places.

The delay has been justified by some of the scientists and policymakers whose expertise have been critical to fighting the pandemic: access to the limited supply of medical face masks had to be prioritised for frontline medical workers. Nevertheless, this is a lame excuse. Once government directives on mandatory wearing of face masks in public places were given, alternative masks made from fabrics – even from homes – emerged.

And, fourth, global coordination of the responses has been abysmal. The spread of Covid-19 has leveraged incompetent leaders who have been peddling populist and nativist ideas to divert attention from their ineptitude. Two prominent examples would suffice. Last month at a political rally he unadvisedly held, President Donald Trump said that he instructed that testing should be slowed in the United States, since more tests would increase the number of new infections! In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro, also a populist demagogue in his own right (pun intended), has, like his American counterpart, refused to wear face mask in public for weeks.

These actions serve to undermine the science of fighting the pandemic in these countries. Unsurprisingly, therefore, U.S. and Brazil are having disproportionately high burden of the disease. With some other global and regional leaders acting in similar – even if less egregious – ways, mustering global actions to fight the virus has been more difficult.

Worldwide, the number of infections is over 10 million, and more than 500,000 people have died from the disease. The spread of Covid-19 has been amplified by control measures that significantly underrepresent what the world should have been capable of. As such, the post-Covid-19 new normal that have been glibly talked about represents a badly laid track that would slowdown the potentials for the global economy to accelerate growth in the near future.

This does not mean the world should return to the “old normal” of pre-Covid-19. If it was a perfect era, the pandemic would not have been this devastating. But it is important to look back at some of the debates about the trajectory of the world economy before the dramatic turn since December 2019. Two of the policy debates up till then were on how to address global imbalances and ensuring the Fourth Industrial Revolution would be humane.

Autopiloting into post-Covid-19 will exacerbate both inequality and the labour issues of hyper automation. Working from home requires new tools, connectivity and skills, as it now is with teaching and learning. But access to the new work and learning tools are not even, or equitable. In countries like Nigeria, the political elite that has disempowered the people through misgovernance and corruption will continue to have undeserved priority access to opportunities, and for their children also. Most Nigerian children, who are from poor homes, will be condemned to intergenerational poverty.

A hyper-digitally-connected new economy that is powered by big data and substantially operated by robots, without addressing the associated labour risks, has been identified as a threat to jobs worldwide. This, in a new normal of remote working, would be something close to waging an economic war against a swathe of the labour force that would be rendered redundant. And if business travels become less important and events mainly hold virtually, what would be done to the thousands of aircraft, motor vehicles (including taxes and buses) and train coaches that are now operating below capacity, or office edifices that are now fractionally occupied?

The delusion of the fanciful new normal should end. After the faltering with the initial phase of responses to the pandemic, there remains the need to competently fight the infectious disease. A second wave of infections in countries that already have tamed the spread of the virus must be suppressed or prevented. The science for this is clearer now: test, isolate, trace and treat. Physical distancing (a term I believe should replace and not be synonymous with “social distancing” as it is more apt) and wearing of face masks in public places should remain mandatory until herd immunity or vaccination of vast populations against the virus is achieved.

The breadth of new investments is also crucial. As entrepreneurs and investors are betting on tech sectors, policymakers must develop incentives for investments in other sectors, especially those that improve food security and provide substantial number of jobs.

The standard prescription is investment in infrastructure to reverse an economic downturn. But this has not worked in Nigeria, after five years of increasing budgetary capital expenditure. The 2020 capex represents more than three-and-half folds increase, compared to 2015. Without local knowhow, and because of excessive borrowing relative to fiscal revenue for the projects, local jobs have been elusive even as the fiscal space has dangerously narrowed. Therefore, developing countries must be practical in their determination of the investments to help reflate their economies, with priority placed on creating sustainable jobs, building fiscal buffers, and strengthening social safety nets.

Finally, any sense of normality requires development, production and global distribution of Covid-19 vaccines. While looking forward to when vaccines against the disease would come on stream, this is the time to start planning their seamless global distribution, by mobilising funding and mapping safe logistics. Coronavirus should not be better at spreading globally than the world is able to coordinate efficient distribution of vaccines against the virus when developed.