Jide Akintunde, Managing Editor/CEO, Financial Nigeria International Limited

Follow Jide Akintunde

![]() @JSAkintunde

@JSAkintunde

Subjects of Interest

- Financial Market

- Fiscal Policy

Buhari's fiscal contradictions 03 Nov 2017

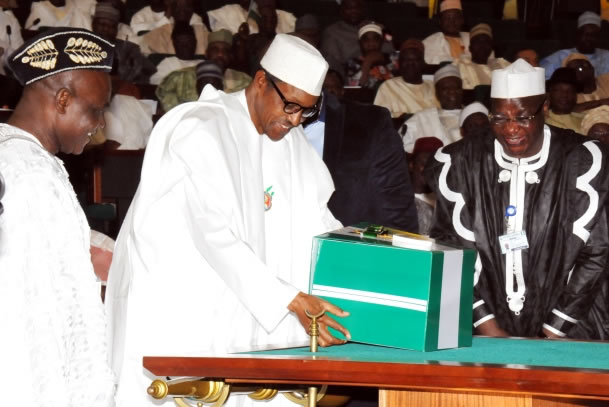

President Muhammadu Buhari presenting the 2016 Appropriation Bill to the National Assembly

The doppelganger of General Muhammadu Buhari has been occupying Aso Rock Presidential Villa since 2015. Unlike the General, who was reputed to be very frugal, his spitting image, President Buhari, obsesses with deficit budgeting. And, in spite of the risk of plunging the country into a frightening debt trap with his massive deficit financing, the execution of his expansionary fiscal policy has been lacking the astuteness of a calculating military general.

President Buhari raised the deficit by 194 percent in 2016 when he made his first budget. From N755 billion in 2015, the fiscal deficit reached N2.35 trillion in the 2017 budget. The deficit is projected to expand further to N2.77 trillion in 2018.

The justification for the fiscal expansion, which has increased the federal government's debt stock by N6.2 trillion in two years (June 2015 – June 2017), was initially to prevent the economy from slipping into recession. That objective failed woefully when, instead of achieving 4.37 percent GDP growth rate forecasted in the 2016 budget, the economy entered recession in Q2 and contracted by 1.5 percent at full year. But with the end of the recession anticipated this year, the 2017 deficit was intended to bolster growth to 2.19 percent. Five months after passing the budget, however, this growth forecast has been revised downward to 1.5 percent.

But was there an alternative to the debt-fuelled growth strategy of the administration? In economics, there are always alternative strategies. The polar opposite of debt-fuelled growth is austerity. But in recent years, austerity measures, in the face of strong economic headwinds like Nigeria has faced since 2015, have been discredited. Austerity measures in the Euro zone fostered protracted very weak growth following the Great Recession caused by the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis. But a quick combination of fiscal stimulus and quantitative easing put the U.S. at the cutting-edge of recovery among the countries battered by the GFC.

Countries who cannot afford the U.S.-styled stimulus, and who want to avoid the negative consequences of austerity, can opt for a policy that is situated somewhere along the austerity-massive stimulus continuum. To be credible, such a measured policy would also have to be context-specific, and with a time span.

The context of the Nigerian economic headwind was the slump in the prices of oil in the international market beginning from H2 2014, coupled with the absence of fiscal savings to call on. In what would have been consistent with General Buhari's parsimonious reputation, but with the good judgement of distinguishing running the national economy from operating his personal finances, President Buhari could have tried to smoothen the economic cycles. This would have entailed raising the deficit level, but to nowhere near as much as he has done. Such a policy, at its most canny, would have to optimise oil revenue generation and value delivery for every naira budgeted.

But alas, President Buhari has in the most basic of ways failed in executing his own strategy. His budgets are never passed on time. The 2016 and 2017 Appropriation Acts were signed into law in May and June of the respective budget years. The 2018 budget has now missed the October 31 timeline the government had insisted it would observe in laying the budget before the parliament.

Perhaps the 2018 budget would still be passed before the end of this year, given that the administration has vowed to revert to the January-December budget cycle in 2018. But this would create an overlap in the implementation of the 2017 and 2018 capital budgets. Indeed, this issue was present with the 2016 and 2017 capex plans. Only N992 billion out of the N1.59 trillion capital budget for 2016 had been released as at March ending this year. By May, total disbursement had increased to N1.2 trillion, according to the Minister of Budget and National Planning, Senator Udo Udoma. Be that as it may, the overlap of budget periods remains a problem that will bedevil the 2018 budget. At the end of October, disbursement for the 2017 capex had yet to reach 20 percent of the total.

The failure of President Buhari's fiscal strategy may have been headlined by its unmet GDP growth projections. However, his deficit financing plan has also proved to be short-sighted. Until now, the government has had little problem raising the domestic component of its deficit financing. But the massive domestic borrowing has overheated the local debt market, raising the true yield on 12-month Nigerian Treasury Bill to 22 percent. Now that the government can no longer afford domestic debt, it wants to rebalance its debt portfolio more in favour of lower-cost external financing, and is in hunt for longer maturities.

But the decision to pivot towards external borrowing may have come a little too late, given the deterioration of the Nigerian sovereign balance sheet on account of the fiscal operation of the past two years. With the ratio of debt-service-to-government-revenue already above 60 percent, foreign lenders would be wary of supplying Nigeria's demand for debt, and we will definitely pay higher interest rates than we would otherwise have had to.

It is in the context of this floundering fiscal plan that the Nigerian debt sustainability is being debated. Without considering an adverse debt-service-to-revenue scenario, the fiscal authorities were out on a limb. They argued (and still are arguing) that the country has significant headroom to borrow, given that the debt-to-GDP ratio is still below 20 percent. But no one is persuaded. The IMF has added its voice to those of various local stakeholders calling for caution with raising the level of the public debt.

The debt repayment strategy of the government is to facilitate infrastructure development. With the infrastructure raising economic growth, we are told “the debt would pay itself.” This argument made some sense when government was borrowing more in naira. Local tax revenue would go up with increased economic activities. When, for instance, the rail lines in which the government is channelling part of its debt financing start to operate, they will generate revenue. But this argument becomes quite bogus with the shift to external borrowing, except local taxes and train fares are going to be collected in dollars.

President Buhari's massive budget deficits are not meeting their growth forecasts. This indicates the futuristic gains of his fiscal strategy are but pipe dreams. More abandoned and uncompleted projects are now adorning the landscape. What is certain now is that the country is being led into a debt trap. With his frugality and discipline, General Buhari that was described to the electorate in 2015 would have done better.