The dangers of herd mentality

Feature Highlight

In response to reports of shots fired, police evacuated two terminals at Kennedy Airport on Aug. 14. The incident turned out to be a false alarm, but potential assailants could use such a tactic to lure people out of safety and into an attack site.

After the attacks over the past six months on airports in Brussels and Istanbul and on a beachfront in Nice, people are understandably on edge. Some 40 people were hurt on the evening of Aug. 14 in the French resort town of Juan-les-Pins when vacationers, mistaking firecrackers for gunshots, caused a stampede in their effort to flee what they thought was a terrorist attack. An ocean away on the same night, police evacuated two terminals at John F. Kennedy International Airport in response to reports of shots fired. The Federal Aviation Administration implemented a ground stop at the airport, diverting flights and causing significant travel delays. Within a few hours, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced that it had found no evidence of gunfire in the terminal, and the airport returned to normal operations. But in the interim, thousands of passengers had been forced out of terminal buildings and then congregated in large crowds.

Both incidents turned out to be false alarms, but they illustrate the ease of inducing panic in crowds of people and how disruptive that panic can be. Perhaps more ominously, the events demonstrate how easily victims might be herded toward an attack zone – especially if security protocols drive people from relatively safe zones into areas where they are more vulnerable.

A Tried and True Tactic

As a hunting tactic, driving prey into a kill zone is a time-honored method that transcends cultures. From Native American tribes herding bison off a cliff to peasants in India driving tigers toward rajahs waiting in ambush, the strategy is likely as old as hunting itself. The concept also applies in conventional warfare – where enemy forces can be pushed, channeled or lured into ambush zones, and in unconventional warfare, too. One of the primary objectives of counterinsurgency is to isolate insurgents so that they can be engaged and destroyed.

Likewise, the method can certainly be used to stage an attack. The two perpetrators of the March 1998 school shooting in Jonesboro, Arkansas, did just that: One attacker set off a fire alarm, and as students and teachers filed out of the school to their designated assembly areas, the pair opened fire, killing five and wounding 10 others. Assailants could intentionally create diversions like those at Juan-les-Pins and JFK to push people toward an ambush. People trying to escape peril would then find themselves unwittingly running toward it.

Don't Panic

During an evacuation like the one at JFK or a scare like that in Juan-les-Pins, it may be difficult to determine where the real threat lies or, indeed, what it is. People must fight the urge to panic in these instances, while also working to avoid large crowds as much as possible. Not only will this reduce the person's risk of being trampled, but it will also help him or her avoid danger in case the crowd itself is the target. Though human nature drives people together for protection during and after an attack, that behavior is a vulnerability rather than a defense in the context of terrorism.

Perhaps the most important factor affecting a person's reaction to a life-threatening incident is mindset. Being mentally prepared to take action if something happens can help keep someone from freezing up or reacting in a mindless frenzy. Even when struggling to remain calm in an evacuation or a perceived attack, people must be mentally prepared for the possibility of a secondary assault. This means continuing to practice situational awareness and trusting your gut when something doesn't quite feel right. By maintaining proper situational awareness and understanding the possibility of being targeted, a person will be better prepared to recognize that an attack is unfolding. The sooner a target understands and accepts that an attack is underway, the better. Similarly, the sooner someone realizes an attack could be directed against a crowd and takes steps to mitigate that threat, the better.

Once a person has recognized that an attack is taking place, he or she must determine where it is coming from and what it is directed against. This is a crucial step that must be taken before someone can decide how to respond; otherwise, a victim could run blindly from a position of relative safety into greater danger. In many instances, the source of the threat will be evident and will not take much time to locate. But sometimes the danger is harder to trace. The sound of gunfire, for instance, can echo depending on the location of the attack (in a building or on the street). Under those circumstances, it may take more time to determine where it is coming from, as the July 7 police shooting in Dallas illustrated, and it is prudent to quickly take cover until the threat can be identified and located. During the November 2015 attack at the Bataclan nightclub in Paris, multiple gunmen stormed the building from different entrances, complicating escape plans.

Keep Away From the Crowd

Adverse situations are often fluid, unpredictable and confusing. Simple adages like "Run, Hide, Fight" (or a new variant that we've come to prefer, "Avoid, Deny, Defend") and "get off the X" can come in handy, since they are simple enough to remember even under duress. But as they heed these sayings, people must also be conscious that their movement could take them into a secondary attack zone. For this reason, they should try to get farther away from the site of the attack instead of milling around just outside the evacuated area in a vulnerable crowd. Leaving the scene, if possible, is safer than standing around in a large group.

After the travelers and airport personnel were cleared from JFK, they were forced to stay in a temporary evacuation area. Many people stood on medians, completely vulnerable to a bombing or drive-by shooting, even though there were several concrete and metal pillars nearby that could have provided shelter against an attack. If confined to an evacuation area, efforts should be made to keep a low profile, move as far away from the crowd as possible and position oneself near objects that could be used for cover. It is also important, under such circumstances, to maintain situational awareness and to try to identify escape routes or places one could lock or barricade against an attacker.

Of course, not every fire alarm or emergency evacuation is a terrorist ambush, and we certainly do not want to promote panic or paranoia, which are detrimental to good personal security. At the same time, however, people should be aware of the possibility of attacks and be prepared to respond calmly and rationally if one were to occur.

Scott Stewart supervises Stratfor's analysis of terrorism and security issues. Before joining Stratfor, he was a special agent with the U.S. State Department for 10 years and was involved in hundreds of terrorism investigations. “The Dangers of Herd Mentality” is republished with the permission of Stratfor and under content confederation between Financial Nigeria and Stratfor.

Other Features

-

The best sites to buy and sell Bitcoin in Nigeria: A comprehensive ...

Buying and selling BTC doesn’t have to be a hassle. Check out to best sites to buy and sell Bitcoin in Nigeria ...

-

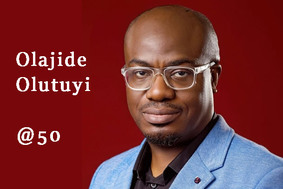

At 50, Olajide Olutuyi vows to intensify focus on social impact

Like Canadian Frank Stronach utilised his Canadian nationality to leverage opportunities in his home country of ...

-

Reflection on ECOWAS Parliament, expectations for the 6th Legislature

The 6th ECOWAS Legislature must sustain the initiated dialogue and sensitisation effort for the Direct Universal ...

-

The $3bn private credit opportunity in Africa

In 2021/2022, domestic credit to the private sector as a percentage of GDP stood at less than 36% in sub-Saharan ...

-

Tinubunomics: Is the tail wagging the dog?

Why long-term vision should drive policy actions in the short term to achieve a sustainable Nigerian economic ...

-

Living in fear and want

Nigerians are being battered by security and economic headwinds. What can be done about it?

-

Analysis of the key provisions of the NERC Multi-Year Tariff Order ...

With the MYTO 2024, we can infer that the Nigerian Electricity Supply Industry is at a turning point with the ...

-

Volcanic explosion of an uncommon agenda for development

Olisa Agbakoba advises the 10th National Assembly on how it can deliver on a transformative legislative agenda for ...

-

Nigeria and the world in 2024

Will it get better or worse for the world that has settled for crises?

Most Popular News

- IFC, partners back Indorama in Nigeria with $1.25 billion for fertiliser export

- CBN increases capital requirements of banks, gives 24 months for compliance

- CBN settles backlog of foreign exchange obligations

- Univercells signs MoU with FG on biopharmaceutical development in Nigeria

- Ali Pate to deliver keynote speech at NDFF 2024 Conference

- NDFF 2024 Conference to boost Nigeria’s blue and green economies