Nana Ampofo, Partner, Songhai Advisory LLP

Subjects of Interest

- Finance and Investment

- Fiscal Policy

- Frontier and Emerging Markets

- Geopolitical Analysis

- Governance

- West Africa

Commodity producers and economic decline in ECOWAS 01 Jun 2015

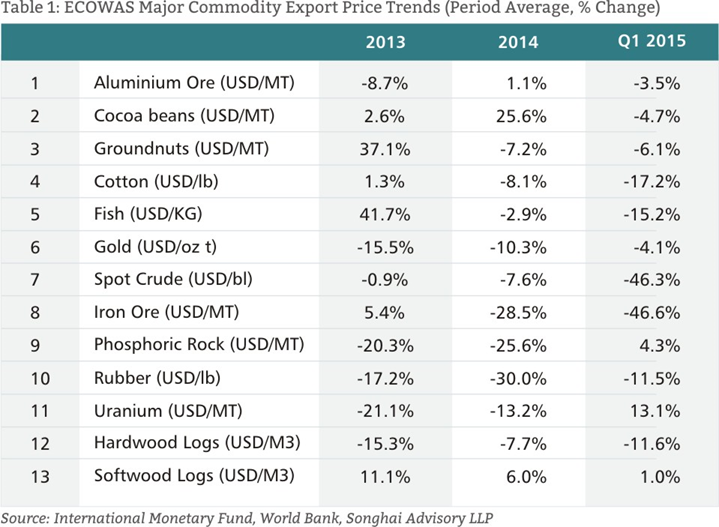

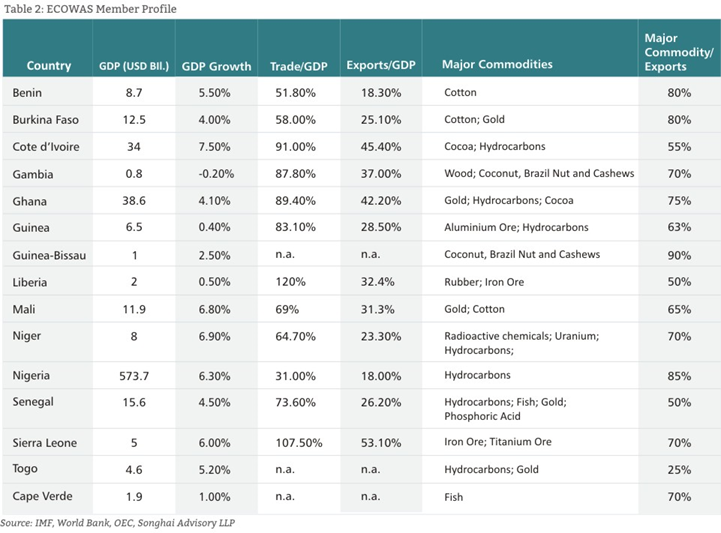

The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) consists of 15 nations, most of which may be described as commodity producers – and profoundly so. As can be seen in tables 1 and 2 below, foreign exchange revenues for ECOWAS countries, from the largest to the smallest, are still greatly influenced by primary commodities. In most instances, there is an outsized effect on government revenues and jobs to be taken into account as well.

This remains the case despite the last decade and a half’s dramatically increased annual FDI and portfolio investment inflows (premised in part on perceived changes in technology, demography and consumption patterns in the ECOWAS countries rather than their natural resource wealth). As such, examining international price volatility of commodities, the impact on local entities and how those entities would respond, should be a strategic priority for ECOWAS member states and companies operating in the sub-region. Particularly given the direction and quantum of change in recent years, and the choppy outlook going forward.

Although it would be a mistake to assume that the end of the commodities super cycle has the same significance for all the ECOWAS members, some of the policy prescriptions and the push back from affected parties will look very similar, indeed. In the interests of time and space, this article will focus more heavily on the Anglophone members.

Macro realities and policy response: Nigeria, Ghana

Accounting for around 80% of the estimated USD720 billion ECOWAS regional economy, it seems logical to start our analysis with Nigeria. First the woes: The unforgiving oil price slide caught in Row 7 of Table 1, alongside anemic growth in the European Union (a major trading partner) and perceived political risk, has contributed to a weakened exchange rate, reduced international reserves, a reduced current account surplus and a stubborn fiscal deficit. It has also contributed to slower GDP growth and some capital flight. To put it in numbers:

• As of May 27, the exchange rate was USD1: NGN199.05 compared to USD1: NGN157.5 in 2012 (this takes account of a partial recovery following the peaceable election result)

• The current account balance was above 4% of GDP and in the black in 2012 but is expected to come in at less than 1% of GDP this year if not negative.

• Total reserves, which were equivalent to USD46 billion in 2012, now stand just under USD30 billion.

• On the balance between revenues and expenditures, we note that the fiscal balance has been in deficit since 2013; it is currently around 2% of GDP. The Central Bank is warning that there must be an “adjustment in expenditure to reflect revenue realities.”

• Real GDP growth was around 6% per annum in 2014 but is expected to fall below 5% in 2015.

The immediate past administration and the Central Bank of Nigeria respectively responded with reduced capital expenditure and new capital controls but the outlook remains uncertain. President Muhammadu Buhari, who took office on Friday, 29th May, has a lot on his hands. With this in mind, the new administration was, before its inauguration, having serious and frank discussions with the private sector about areas of reform e.g. power and petroleum sectors, according to a policy specialist speaking at the recent Oxford Africa Conference. Re-visiting that most-difficult aspect of the petroleum sector reform – which has to do with subsidies – looks all the more pressing.

First step would have to be a public education programme such as has preceded the introduction of Value-Added Tax/General Sales Tax (VAT/GST) in neighbouring jurisdictions. In this instance, Nigerians need to know why they must pay more for a product and service which would be available and for the next five years or so will provide patchy but slowly improving service quality. On tax, with revenues at 12% of GDP, domestic revenue mobilisation is also likely to receive attention – particularly raising tax revenue and plugging “leakages”.

The slide in fortunes has been even more dramatic in Ghana where theoretically, economic diversification is more advanced. Or at least, rather than relying on a single export commodity, Ghana has three – gold, cocoa and oil (Table 1 Rows 2, 6 and 7). Nevertheless, real GDP growth has gone from a high of 14% in 2011 to 4.2% last year and the Ghana Cedi fell 31% against the dollar in 2014 alone (making it one of the worst performing currencies in the world in 2014). Meanwhile, the current and fiscal accounts are in deep deficits (both hovering above 9% of GDP). Here too, capital controls introduced by the Central Bank have had only limited impact on currency fluctuation. And while the government has been serious about domestic revenue mobilisation through VAT and other levies, the deficit remains stubbornly high. The why of this may lie in the fact that in the round, Ghana’s difficulties are rooted less in the collapse of export receipts (particularly gold) than the following:

• A dramatic increase in expenditure on public sector wages

• Similarly significant increase in expenditure to meet domestic debt obligations

• Oil production, and the revenues thereof, never reached the levels imagined.

Consequently, the 2015 budget and the IMF programme adopted in April this year target a broader malaise than declining international commodity prices, though that’s certainly part of the picture. They imply freezes on hiring in the civil service, aggressive vetting of the payroll to remove ghost workers and a miserly approach on the provision of government guarantees. Over the medium- to long-term, officials are betting on new oil production from 2016-17 onwards and associated gas to turn the tide. (Though there is the concern that the on-going maritime border dispute with Cote d’Ivoire could undermine a significant proportion of Ghana’s future oil wealth.)

Perfect storm

Declines in the value of iron ore, timber and rubber resources have hit the short- and indeed medium-term outlook for Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea (see Rows 8, 10 and 12 of Table 1). Their dilemma has been compounded by the tragedy of Ebola, which has claimed more than 4,000 lives in Liberia, just under 4,000 in Sierra Leone, and almost 2,500 in Guinea since March 2014. More than even these numbers can show, Ebola put a break on normal economic activity from which these countries have not yet fully recovered.

All the Mano River countries have been affected but the reversal is most evident in Sierra Leone. In 2012 and 2013, Sierra Leone was amongst the fastest growing countries in the world with estimated real GDP growth of 15% and 20% respectively. Last year, its GDP growth fell to 6%. This year, the economy is expected to actually shrink in size owing to crisis at African Minerals and London Mining, the country’s two major iron-mining companies. In Liberia and Guinea, the trend is of a similar shape but the peaks and troughs are more moderate.

The tragic perfect storm of reduced commodity prices and Ebola mean that the benefits of recently implemented structural reforms to attract private investment and increase government revenues are now muted. Looking forward, combating Ebola and its impact on the citizenry is still the immediate focus of attention for domestic governments and their international development partners. Over the medium term, infrastructural development and regional integration will feature more heavily.

Conclusion

It is very unclear what path commodity prices will take over the next twelve months. But the commodities super cycle that has acted as a catalyst for growth in many of the ECOWAS countries has weakened, if not died. Many observers are rounding down their growth projections for the sub region – more so than for our more diversified sister economies in East Africa. That being the case, one might rightly deduce that here in the ECOWAS region, our potential would be more easily met if we accept that public policy decisions that we are faced with are complex and/or difficult, and then go ahead to confront them boldly. For instance, the attenuation or removal of subsidies in Nigeria, civil servant pay restraint and stubbornly high regressive taxes in Ghana, or regional integration and economic recovery in Mano River markets are tough issues. We should, however, be encouraged that in comparison with previous cycles e.g. 1980s-90s trough, thus far, ECOWAS countries have wobbled but not fallen under the pressure.